Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Buying used - Suzuki GSX-R1100

(May 2020. See the model gallery near the end.)

by Guy 'Guido' Allen

See our GSX-R750 series feature here

In a class of one

Suzuki’s mighty GSX-R1100 has plenty of fans – let’s take a look at how they stack up in the used market

Sure it may have been mown down in the stampede of newer and shinier models over the years, but in 1986 the GSX-R1100 was (as Motorcyclist magazine over in the USA then described it), “The quickest, baddest production big-bore sportbike you can buy.” It scorched down the standing quarter in 10.65sec with a 130mph (209km/h) terminal speed and had tripped the top speed radar at 258km/h. And it weighed an incredibly light (for its day) 197kg dry.

The other makers soon played catch-up, with the Yamaha

FZR1000 being the next serious competitor but, for a

little while there, Suzuki had what was effectively a new

category – litre-plus supersports multis – to itself.

Project engineers of the day admit they often wandered

into uncharted waters in the making of this bike and its

equally revolutionary 750 sibling (released the year

before), which meant taking a few development and

marketing risks.

Did it pay off? Well the name GSX-R effectively became a

brand in its own right, though there’s no doubt there were

some ups and downs along the way where the company,

according to some, may have lost its way.

So which are the models to buy and how do they stand up to

scrutiny? Let’s first get a bit of a handle on what came

out and when.

History

There were essentially four major generations of the

mighty GSX-R1100: three air/oil-cooled and one

liquid-cooled.

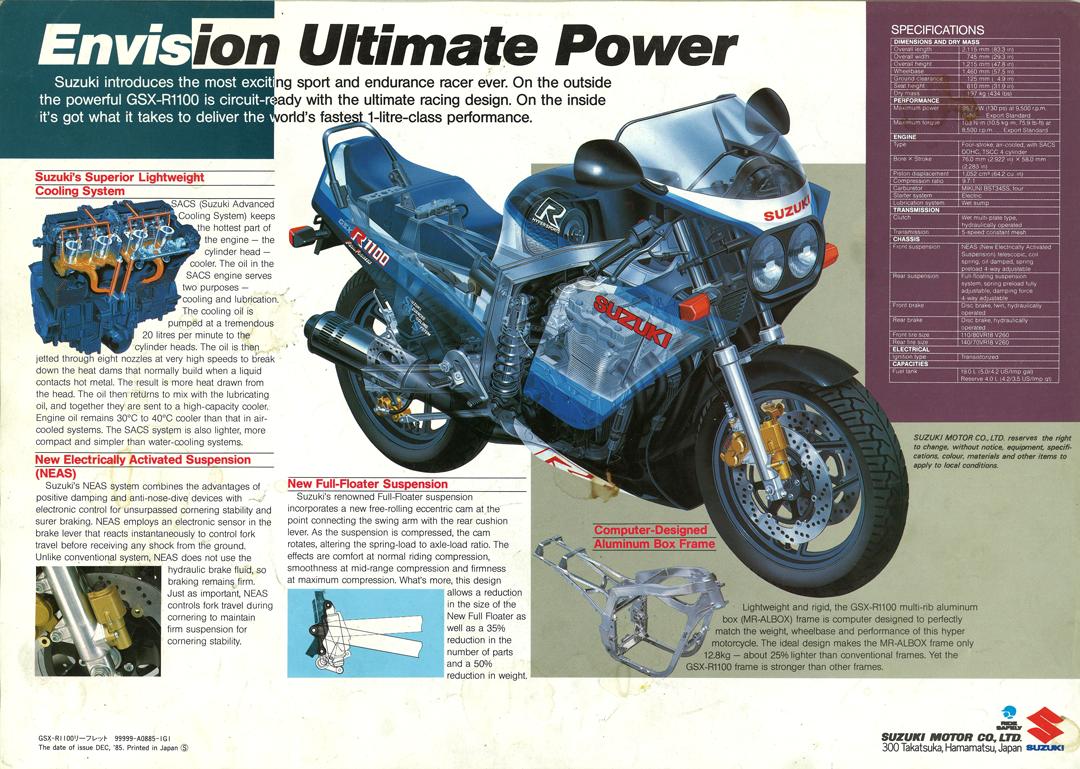

Gen one was the G, H and J models, all of them notable for

their slab-sided styling and running the original 1052cc

powerplant, quoting 130 horses. Essentially a development

of the 750, it ran a reinforced frame, longer swingarm,

more relaxed steering geometry up front and a

non-adjustable steering damper.

Little was wrong with the first iteration of the machine –

which says something for the quality of the development

process – and so the changes for year two (H) were nil

other than colour.

Year three (J) scored Enkei three-spoke rims that lifted

the looks of the machine and gave it a slightly wider

contact patch on the rear. The front guard was widened a

little, while the only engine mod was increased capacity

for the massive front oil cooler. The sidestand also came

in for attention, to make the bike a little less prone to

tipping over. Just on 2kg was added to the dry weight in

the J version.

Generation two was the K and L series of 1989-90. This one

scored a lower and heavier chassis, with some similarities

to the 750 Slingshot of 1988. We got to see the big

version of the engine, 1127cc, which in turn saw power

jump to 143 horses (138 in Oz, thanks to different noise

regs). Torque increased by close to ten per cent at

11.6kg-m. Weight was up to 210kg and we were now on

17-inch rims.

The K copped a roasting from some commentators that saw

next year’s model, the L, score significant changes

instead of the usual second-year paint swap. These

included upgraded suspension (USD at front), longer

swingarm and a switch to Michelin rubber, which was made

wider at the back.

Gen three was the 1991-92 M and N series and this was a

final period of refinement with the air/oil engine, rather

than radical change. The powerplant had numerous

alterations, including a switch from forked rockers to

single arms and shim adjustment. Carburettor size

increased massively from 36mm to 40, though the power

increase from 143 to 145hp was only slight. Meanwhile,

weight had climbed to 226kg.

Suspension was given a major make-over, boasting more

comprehensive adjustment front and back, along with a

greater choice of rates. Even the gearbox wasn’t left out,

scoring cooling oil jets on the top three cogs. Visually,

it’s marked as the first time the headlights were enclosed

behind a screen, for cleaner aerodynamics.

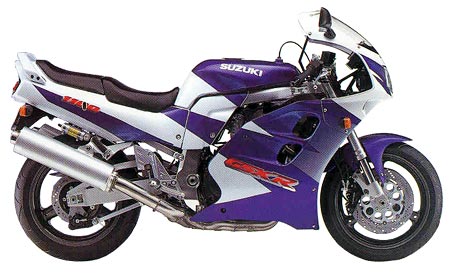

Generation four (WP through to WU) was last hurrah and,

once again, it followed the development of little brother

750 – this time by adopting what was now regarded as a

more conventional liquid-cooled engine.

The cooling allowed Suzuki to be more ambitious with the

power output (155 horses) and many tuners felt there was a

lot more potential locked away in those cases. Sadly

weight was also up. At 231kg claimed dry, it was a figure

which threatened to nudge it closer to sports tourer

rather than pure sports bike territory. Production ceased

in 1998.

On the road

In their day, the original slab-sided Gixxer elevens were

a very impressive device, particularly if you happened to

have a nice big and open set of sweepers to play on. I

remember having some near-religious experiences on the

things when they were new, one of which I’m sure involved

former AMCN Ed Ken Wootton (RIP), an FZR1000 and some acts

he described as an unsanctioned race meeting.

Anyway, even by modern standards the G through to J models

felt steady, fast, and strong. The suspension was nowhere

near as good as the top modern kit but nevertheless coped

well. Today, it would feel a little old fashioned, and

down on grip, but a well set-up one should still be a

damned good ride. That’s assuming you can cope with the

sports-style ride position, which is at its most harsh on

this generation.

I’m less enamoured with the middle air/oil-cooled series

of K through to L, despite the numerous suspension

upgrades along the way. Oh, and the significant jump in

engine performance. Don’t get me wrong, in anything other

than extreme circumstances, they were actually very

capable machines. But somehow they lacked the brutish

character of their predecessors and didn’t ‘gel’ as well

into a complete working unit. Straight line performance

was near identical to the earlier versions.

For me, the M and N models brought the whole plot together

again, albeit in a package that felt very different to the

one the company started out with. Though still appallingly

fast, they felt heavier and a little less happy in a true

sports environment.

As the heaviest of all the Gixxers, the liquid-cooled W

series had gained a whopping 39 kilos over its first

ancestors. Okay, it also picked up an extra 26 horses

along with a smoother and more sophisticated engine. But

any pretence of it being a track weapon was long gone.

Which is okay, as it still made a very quick and capable

road bike – one I have a lot of time for.

It’s still very fast by today’s standards and can be made

to handle respectably with a basic freshen-up. Just don’t

expect it to be competitive on the track with a modern day

supersports. It is however a super-capable sports-tourer.

In the workshop

A few calls around the place and a scan of the web

revealed remarkably few mechanical dramas with these

things. Across the range, the engineering seems to be

robust.

Few saw the race track locally, as they were ineligible

for anything other than unlimited classes – which meant

club rather than national championship events. So the good

news is most will have spent little time being ridden at

their limit.

Regular changes with good quality oil is essential for

long engine life, particularly given the sophistication of

their cooling systems. High milers will be looking for a

fresh camchain at around 100,000, at which point you might

be tempted do the rings and valve guides. I’d be backing

the liquid-cooled powerplants to last the longest, if the

maintenance is kept up.

The later generation machines on 17-inch rims are much

easier to find a good selection of rubber for – 18-inch

choices are limited.

Check carefully for the condition of the bodywork on the

older machinery, as replacements are becoming scarce.

Poorly done or cheap modifications are also something to

be avoided. If it’s got an aftermarket exhaust, for

example, check it’s running right and that the owner has

made an effort to get it tuned properly for the pipe.

It’s a fair bet that the suspension will be worn on almost

anything you look at, so keep in mind the possibility of a

rebuild, which is worth doing on anything with this sort

of performance.

Which model?

At the moment, that may depend on whether you’re a

collector or a bargain-hunter. If you’re the former, the

first three models (G, H and J) are the pick. Some folk

like the J as the ultimate slab-side model, while others

will stick with the very first G. In any case I’d be

looking for the best machine available, to minimise

ongoing restoration costs. Here, the condition of the

cosmetics could be just as important as the mechanicals.

Prices are all over the place for early models, but about mid teens would seem right for a decent one. A concours G could nudge $20k.

If you’re looking for a good-value ride, my choice is any

of the late W series. You can pick up a decent one for

around $6000-8000. That’s bargain motorcycling,

particularly considering the stupendous power output, and

you can fit some good current rubber to it. Increasingly,

collectors will start to eye any generation as desirable.

Regardless of model, pay the right price for a good

example, and you’ll have more than enough performance to

keep you interested for a very long time.

See the contemporary FZR1000-GSX-R1100 comparo from Classic Two Wheels

***

Know your Gixxer

1986 – G model

The original “slabbie” with 130 horses and 197kg claimed

dry weight. This was an early adopter of radial tyres, on

18-inch rims – 110/80-18 up front and 150/70-18 on the

rear.

1987 – H model

Unchanged except for graphics.

1988 – J model

Most obvious change was to three-spoke Enkei rims with a

larger 160-section rear. Oil cooler size was boosted and

dry weight was up to 199kg. Considered highly collectible

as the best-sorted of the slabbies.

1989 – K model

Complete redesign with more rounded styling. Engine

capacity up from 1052 to 1127cc while carbs went up from

34 to 35mm Mikuni. Power was now 138hp for 210kg weight.

Now on 17-inch wheels with 43mm forks (up from 41mm).

1990 – L model

Significant chassis changes to counter complaints about

the handling of the K. Included were USD forks and a

longer wheelbase.

1991 – M model

Significant engine and chassis changes. Power claim was

the same, but weight was up to 226kg. More sophisticated

suspension mated to bigger rims. Styling put the

headlights behind a perspex screen for the first time.

1992 – N model

Unchanged except for graphics.

1993 – WP model

The last big redesign, this time with a liquid-cooled

rather than oil/air-cooled engine, in line with a major

change to the 750. Around 155 horses and 231kg.

1994-1998 – WR, WS, WT & WU models

Unchanged except for graphics. Production ceased in 1998,

though they sold locally to 1999. Replaced by the

GSX-R1000 for the 2001 model year.

***

Resources

See our GSX-R750 series feature here

Books

Suzuki GSX-R – a legacy of performance, by Marc

Cook

Published by David Bull Publishing in 2005. A Suzuki

America-sponsored backgrounder on the development of the

GSX-R series that’s particularly enlightening about the

early development years.

Suzuki GSX-R by Mike Seate

Published by Motor Books. History and development

overview.

Suzuki GSX-R Performance Projects by local

author Ian

Falloon

Published by Motor Books. Covers basic servicing along

with a few upgrades that might be tackled at home.

Web

Suzukicycles.org

Excellent index of Suzuki models over the years.

Spex

Suzuki GSX-R1100G (first model)

ENGINE

Type: air/oil-cooled inline four with four valves per

cylinder

Bore and Stroke: 76x58mm

Displacement: 1052cc

Compression ratio: 10.0:1

Fuel system: Mikuni BST34SS x 4

TRANSMISSION

Type: 5-speed constant mesh

Final drive: Chain

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR

Frame type: Twin-loop alloy

Front suspension: 41mm conventional fork, electronically

activated damper

Rear suspension: Monoshock, preload and rebound damping

adjustment

Front brakes: 4-piston 310mm floating twin discs

Rear brake: Single disc

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES

Dry weight: 197kg

Seat height: 810mm

Fuel capacity: 19lt

PERFORMANCE

Max power: 130hp @9500rpm

Max torque: 10.3kg-m @8000rpm

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact