Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

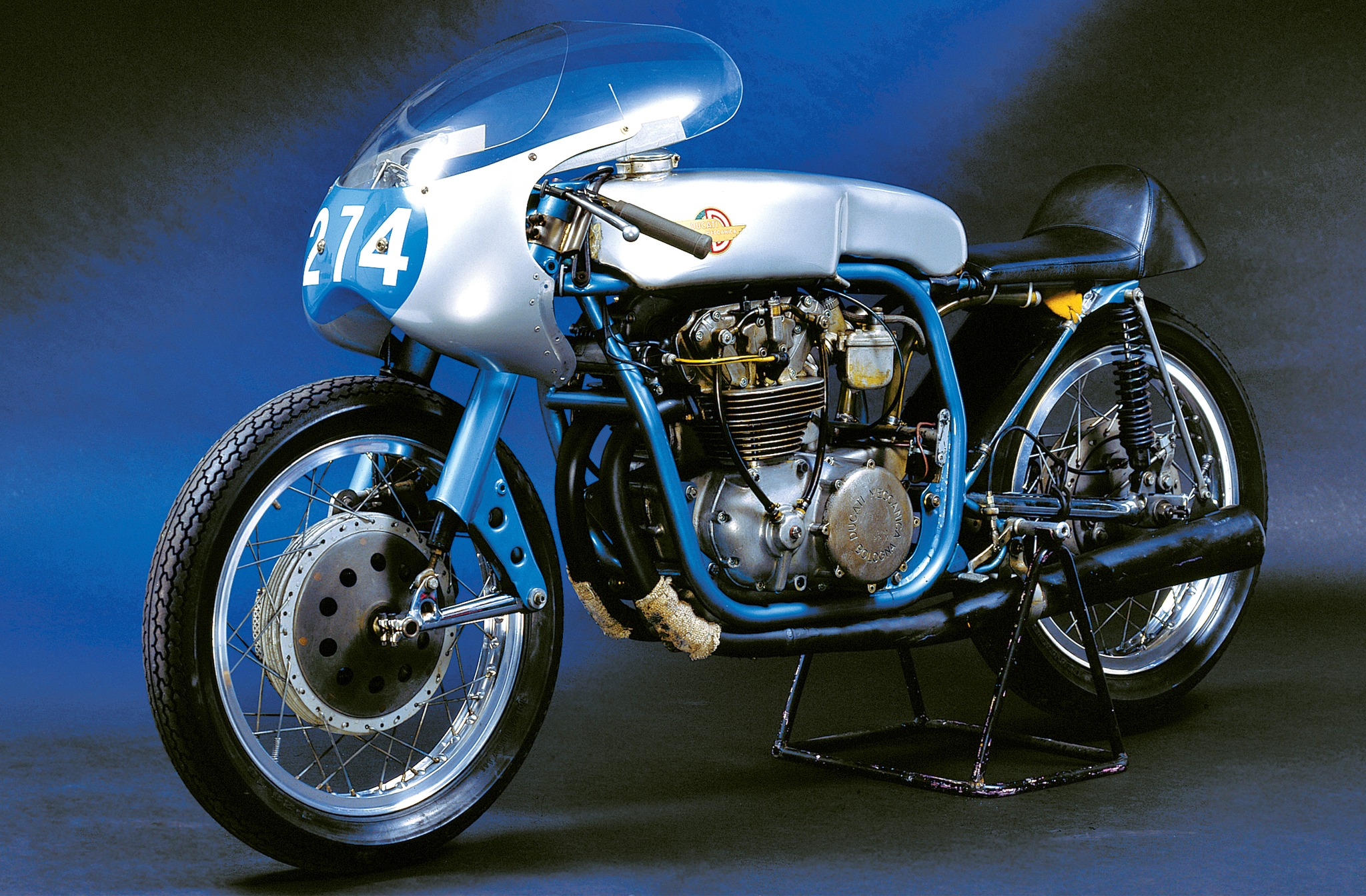

Hailwood's Ducati 250

(by Ian Falloon, Apr 2022)

The

troubled history of Ducati's parallel twin racer

Many

followers of Grand Prix

racing believe the greatest rider ever was Mike

Hailwood. Hailwood could ride

any motorcycle to its limit, and won races on several

makes, in a variety of

displacements, often in the one day.

In 1959 and

1960, he won all

four British titles (125, 250, 350 and 500). While best

known for his nine

world championships on Hondas and MVs, it was Ducati

that Mike was associated

with at the beginning and end of his motorcycle racing

career.

Hailwood’s father Stan

was a wealthy

businessman, and would spare nothing to see his son

succeed in motorcycle

racing. He established a team, Ecurie Sportive, to

further Mike’s career, and

purchased a double overhead camshaft (Bialbero) 125

Ducati Grand Prix single

from then British Ducati agent Fron Purslow during

1958.

In those

days Mike seemed

more interested in playing jazz than racing motorcycles

and he suffered

criticism through having a millionaire father who

provided the best equipment

and tuners. However, he quickly overcame this and

established himself as an

extraordinary talent.

Mike’s first ride on the

Bialbero was at the

Dutch Grand Prix in June 1958, and he finished tenth.

He went on to win three

races on it that year before Stan visited Italy and

arranged to take over the

distribution of Ducati motorcycles in England. In

return, he was able to obtain

a pair of factory 125 desmo singles, and the services

of factory mechanic Oscar

Folesani, for the 1959 Grand Prix season.

Hailwood was

also provided a

factory-prepared 125 desmo twin for selected events.

Soon after receiving the

desmo single Hailwood rode it to victory at Snetterton,

the first win in

England by a desmodromic Ducati. He followed this with

eleven victories in England

that year.

While the little desmo

single provided Hailwood

with his first Grand Prix victory (at Ulster), and

third in the 1959 125 cc

World Championship, Mike was always a little too large

for these diminutive

machines. Stan Hailwood believed Mike would be more

suited to the larger

capacity classes. At that stage, Mike’s 250 cc racer

was an ageing Mondial

single and Stan reckoned a Ducati twin would be the

business.

By 1959, the Ducati twin

had already been around

a few years, both as a 125, and 175. Back in 1950,

Taglioni sketched a plan for

parallel twin, and he eventually found the time to

produce a 175 twin during

1956. This was displayed at the Milan Show at the end

of the year, and Leopoldo

Tartarini raced it in the 1957 Motogiro d’Italia. He

retired with ignition and

generator problems during the third stage.

The 175 set

the basis for all

the racing parallel twins in that it featured twin

overhead camshafts driven by

a train of spur gears from a jackshaft between the

cylinders. There was a pressed-up

crankshaft consisting of two flywheel assemblies clamped

by Hirth (radially

serrated) couplings.

Complex and

difficult to work

on, the engines were beautifully constructed, with the

flywheels and big-end

assemblies machined from solid and all the gears drilled

for lightness. There

was dry clutch and exposed hairpin valve springs but

still a wide 80-degree

included valve angle. With an 11:1 compression ratio and

18 mm Dell’Orto

carburettors, the 49 x 46.6mm 175 produced 22bhp at

11,000 rpm. By 1959, this

was increased to around 25bhp but the powerband was too

narrow, the 112kg

machine too heavy, and it suffered in comparison to the

single.

Stan Hailwood persuaded

Ducati to produce an

updated 175 twin early in 1959. With a new frame, rear

suspension, and Amadoro

brakes Mike tested this revised 175 at Brands Hatch in

March. He wasn’t

particularly impressed and didn’t race it. Stan

Hailwood subsequently sold the

175 to Arthur Wheeler, but remained convinced a

larger, desmodromic, version

was worth persevering with. During 1959, Mike also had

the 125 desmo twin for

certain races, and while this wasn’t especially

successful Stan purchased two

from the factory at the end of 1959.

By this stage, Stan had

persuaded Taglioni to

produce a 250 cc twin, essentially two of the

successful desmodromic singles

doubled up. Ducati had officially withdrawn from

racing by this stage and

undoubtedly Stan Hailwood paid handsomely for this

specially commissioned

racer.

The 250 twin

was first

revealed in February 1960, but when Hailwood first flew

out to Italy for

testing it wasn’t ready. Later in February, both he and

Franco Farnè rode it at

Modena and were apparently satisfied with the machine.

The 250 shared its

55.25x52 mm dimensions with

125 single but in other respects it was a scaled up

125 desmo twin. It had a

six-speed gearbox and twin Dell’Orto 30mm SS

carburettors with flat float bowls

similar to the 125. The power was 43bhp at 11,600rpm

(at the crankshaft) and

provided the 250 with a top speed of around 218km/h.

A unique

feature of the twin

was the ability to remove one side of the engine leaving

the other intact.

Unfortunately, the engine was too powerful, and too

heavy, for the scaled-up

125 double cradle frame, even with Norton forks and

Girling shocks. The brakes

were Oldani twin leading shoe (220mm and 200mm) but the

machine was

considerably overweight (a claimed 112kg but plainly

optimistic) and suffered

from poor acceleration.

At the end of March, the

250 arrived in England

and Hailwood gave it a sensational debut at the

Hutchinson 100 at Silverstone

on 9 April when he won the 250 race. Although Hailwood

won the 250 races at

Brands Hatch and Snetterton, he soon found that while

the new Ducati was

competitive on the faster circuits it didn’t handle

well on the shorter tracks.

The machine

was sent back to

Italy for a new frame, and it arrived back in time for

Mike to win the

international race at Silverstone at the end of May.

Although the new frame

still didn’t solve the handling problems, after the Isle

of Man, Hailwood

elected to ride the 250 at the Belgian Grand Prix Spa

and came fourth.

He then took

the 250 to a

five consecutive victories on British short circuits

before Ulster Grand Prix

where the 250 appeared with another new frame. Stan

Hailwood commissioned this

new Reynolds 531 frame from Ernie Earles in Birmingham,

lengthening the

wheelbase from 1314 mm to 1,72 mm, and lowering and

moving the engine further

forward. Hailwood came fourth at Ulster but he still

wasn’t overly impressed

with the handling.

Apart from

Snetterton (where

he won on the 250 twin), Hailwood chose his Mondial for

the rest of the 1960

British season. Hailwood did ride the 250 twin early in

1961, winning again at

Snetterton but was disqualified at Silverstone as he was

entered on the

Mondial.

When Mike received a

works Honda contract Stan

sold the Ducatis, and John Surtees purchased both the

Hailwood 250s during

1961. Surtees recognized that the Ducatis were

powerful if underdeveloped, and

installed the engines in Ken Sprayson Reynolds frames

with leading link forks

as already built for the Hailwood 350.

Initially

the Ducatis were

for John’s younger brother Norman, who raced the 250

several times towards the

end of 1961. Before the 1962 season a new frame without

a lower right frame

tube was produced but Norman had little success with it.

John Hartle was set to

ride the twin in 1963 but this didn’t eventuate, however

Mike Hailwood gave the

250 one final victory at Mallory Park at the end of

March. Hailwood’s final

ride on a Ducati until 1977 was at Silverstone in early

April 1963 where he

rode the Surtees 250 twin to second behind Redman’s

Honda.

The desmodromic twins may

represent an

unfulfilled era at Ducati, but the 250 (in the hands

of Mike Hailwood) won

enough races to ensure an important historical place

in Ducati’s racing

history. Considering the amazing success of the

desmodromic singles, it was

surprising that Taglioni decided to pursue the path of

weight and complexity

with the twins.

He obviously

believed that

more horsepower was needed to win Grands Prix but

somehow lost direction by

creating a design that was excessively complicated. The

parallel twin

experience also showed that Ducati didn’t have the

resources to produce and

develop one-off racing bikes to order.

Possibly

these projects were

accepted as the economic circumstances at the time were

so difficult any

commissions were welcome. Unfortunately doubling up the

existing successful

singles was a recipe for disaster and what was really

needed was a completely fresh

approach. The twins were plagued with troubles from

fractured crankcases,

broken gears, and electrical and ignition problems.

They may

have been

sophisticated designs but their complexity made them

problematic, and their

power taxed a chassis that was inherited from lower

powered and more balanced

designs. If nothing else, the parallel twin episode

convinced Taglioni on the

virtues of light weight, balance and simplicity, almost

to the point of

obsession. All his later attempts with multi-cylinder

racers were half-hearted.

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact