Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Gold Standard

(written 2018, published here Oct 2020)

by Guy ‘Guido’ Allen; pics by Ben

Galli Photography

Honda’s mighty CB750-Four hit its golden anniversary in 2018 and we took time out with one of its most fierce rivals – Triumph's T160 – to look back to see if it deserves its legendary status

If you happen to own a modern four-cylinder performance motorcycle, 2018 was the year you should have felt free to go out and buy yourself a Honda shirt – regardless of the brand of your mount. Why? Because half a century ago, brand H was in the throes of launching what is widely regarded as the first modern ‘superbike’, the CB750-Four, and very much the forebear of what you’re now riding.

Speaking of riding, we managed to get together two arch-rivals from the period, the most popular variant of the CB750, the K1, and the ultimate version of Triumph’s Trident, the T160. One effectively killed off the other in the market.

When it comes to multis, other makers – including Hendersen (USA – 1931 model above by Mecum), Fabrique Nationale (Belgium) and Ariel (UK) – had produced four-cylinder production motorcycles across the preceding decades.

What made the Honda special was that, in 1968-69, it took mass-produced high-performance motorcycles to another level on several fronts: performance, finish, reliability and accessibility. It wasn’t cheap to buy at around $1500, but it was affordable for many.

The impact of the Honda was such that it effectively hurried the demise of the British industry, in part by sucking most of the oxygen out of the all-important USA market.

While the Brits had multis of their own – like the triple-pot BSA Rocket III (1969 model above, by Mecum) and Triumph Trident – they were simply outgunned. It didn’t necessarily have to be that way. BSA and Triumph in fact had the jump on Honda, with a triple-cylinder 750 powerplant designed by Bert Hopwood and Doug Hele running by 1962. In theory, the company could have had a 750 multi in the market by 1963-64, giving a very useful marketing and development jump on Honda. But it wasn’t to be.

Based on the existing Meriden twins, the triple engines (the Triumph version originally had a vertical engine block, where the BSA variant was canted forward) were a pushrod design, initially with kickstart only, and were eventually launched to some acclaim in 1968.

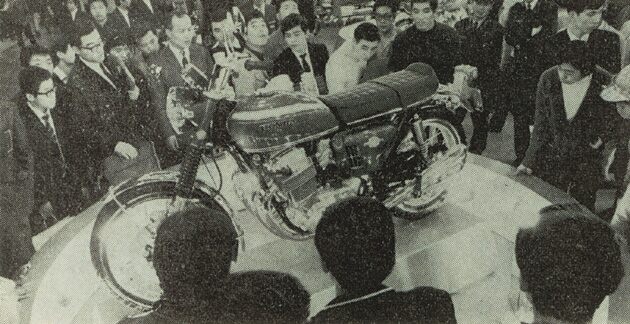

Honda showed its overhead cam four just a month later at the Tokyo Motor Show (above), with electric start, claiming the first front disc brake on a production motorcycle and a 10 per cent power edge. It effectively pulled the marketing rug out from under the Brit bikes.

(Ed's note: Okay, the 'first disc brake' boast is up for debate and it's always risky making these claims. We're told Douglas and Lambretta preceded this. However there is some debate over the 1920s Douglas design, which worked on the outer rim of a disc and was very different to what we now understand as a disc brake. Lambretta's TV175 scooter from the early 1960s used a true enclosed disc brake design, that looked a little like a drum from the outside. It had similarities to the 1980s enclosed discs on Honda's VT500 and CBX550. Can we agree on the CB750 having the first disc brake on a large-capacity volume production bike? Yes.)

Not only did the specs look impressive, but the looks were truly gob-smacking, with four ‘organ pipe’ headers dominating the front of the machine, and four giant mufflers hanging off the rear. Talk about making a statement! It may have been a little garish for English tastes, but that wasn’t the target market.

From day one, the CB’s prime target was the USA. Honda had already made inroads with its famously lively CB450 ‘Black Bomber’ twin, and it clearly wasn’t afraid to innovate. A scan of the company’s GP racers from the sixties will soon confirm that: from the 250cc inline six RC166 through to the 125cc inline five RC149 and its shrieking 23,000rpm redline.

When Soichiro Honda announced he wanted to develop ‘the King of Motorcycles’, it was Honda USA staffers he listened to most carefully. Chief among them was Bob Hansen, the Eastern Region Manager and ringmaster for the CR450 Daytona race team of 1967. His view was that a twin would no longer cut it – what Honda needed was a four.

The turn-around was incredibly quick. In six months from early 1968, a team led by two key figures produced the CB prototype in time for the October Tokyo Motor Show. They were: Yoshiro Harada, the head of R&D, and stylist Einosuke Miyachi. It was on sale in the USA by June 1969 and, despite sometimes serious teething troubles with early examples, was a runaway success.

There’s a cute story published by Motorcyclist magazine, when it judged the CB750 to be the bike of the 20th century: “Mr Honda was famously short with praise, yet even he couldn’t conceal his excitement after riding the CB750 for the first time. One former Honda R&D employee remembered the scene: It was during final testing in the US, Mr Honda happened to be there. He said ‘let me ride that thing’ and just jumped on and blasted off across the desert. He was gone for nearly a half-hour. Everyone was quiet, and very nervous. When he came back, he just said, ‘What a terrific, terrific machine!’ then walked away, laughing. That was the first time anyone there ever heard any words of praise from him!”

Clearly lots of people agreed with Soichiro’s judgement, with a phenomenal 53,400 machines produced in the first K0 generation, topped by 77,000 for the K1.

What was so spectacular? In reality the engineering wasn’t revolutionary. Several manufacturing centres around the world had the capability to produce the technology in the CB. No, it was the combination and packaging that was remarkable.

At the bike’s heart was an air-cooled overhead cam inline four, with two valves per cylinder and running a dry sump. It initially produced around 67 horses, though that was wound back closer to 60 by the K2 series and was cranked up again for the F1 in the mid seventies.

The five-speed transmission was integral with the powerplant and was one cog more than generally being run by the competition.

In reality, there was some car thinking: build in plenty of strength, including a robust electric starter.

For the chassis, the high-point was the disc front brake which had serious bragging rights even if its performance was arguably no better than a decent drum in many circumstances. The twin-loop steel frame used conventional and not particularly high-quality suspension and the package really struggled to cope with the spectacular 120mph (200km/h) top speed.

While the 750 was comprehensively outshone by Kawasaki’s legendary Z900 in just a few years, the Honda remained a player in the big bike market for close to a decade. Meanwhile arch-rivals Triumph and BSA quietly sank.

Whether the Brits deserved their fate is open for debate. Certainly their issues had as much to do with management own-goals as any other failing. So it’s entertaining after all these years, to put the two old rivals back together, near enough to 50 years down the track.

The bikes you see here are arguably in their ultimate production forms. The K1 hails from 1971 and by now has the reliability issues which plagued the early K0s pretty well fixed. It also happens to be the biggest-selling model of the entire series.

Meanwhile the Triumph is a 1975 T160. That means it runs the BSA-configured engine, with the canted-forward cylinders, a transmission upgraded to five speeds and, finally, electric start! Oh, and by now of course we’re running disc brakes at both ends.

With the Trident we have a package that on paper at least should be competitive with the Honda. And it is. It’s fast, brakes more or less the same, and handles far better. That in fact is one of the big differences. On a curvy road, there is no doubt in my mind the T160 is quicker. You can ride it surprisingly hard and it will hold a line.

By comparison the Honda is a big fast cruiser and you could well imagine it being completely at home on a USA interstate, treating the speed limit with fairly scant regard. Of the two, it feels a little more like a modern bike (which is largely down to the engine), even if the handling tends to fall away as the roads get tighter and more challenging. And it’s definitely the one you’d choose for a long trip.

You can see the appeal of both machines. However with a more robust package and a general demeanour that made motorcycle travel more of a pleasure and less of a challenge to the breakdown gods, you can understand how the Honda won the battle in the market.

Does it deserve the near-deity status it has in motorcycle circles? Probably. When you think back to the late sixties, a motorcycle that really could be relied on to start with a button every damn morning, and sit on the proverbial 100 miles per hour without fuss was a fantasy. Until Honda came along…

(Author's note: In case you're wondering where my own preferences/prejudices lay, I own both the CB750 and T160 in the main photo shoot.)

***

My time with CB750s

It says something for the impact of Honda’s CB750-Four

that, a decade after its launch, my purchase of a

second-hand one of these monsters was commonly greeted by

riders of more traditional twin-cylinder bikes with the

epithet, “It’s just a car with two wheels, mate.” And

that, really, was the key to its success.

Yes, for many, it was truly alien in concept. Hit the

starter and just go, reliably.

My K2 suffered an owner-induced engine failure, which meant I got to know the internals far better than you should. The architecture was simple enough and rebuilding one at home from the crank shells up (which were coded for each journal) was entirely possible, so long as you took care.

There were two traps for young players. The first was the oil galleries to the head were incredibly narrow, so any injudicious use of gasket cement could be rewarded with a blocked gallery and chewed-out cam. The second was lots of long duration cams were sold for these things, but inattentive owners didn’t always cut the required relief sections into the tops of the pistons, with disastrous results.

While the engine was simple enough to work on, getting it in and out of the frame was an acquired art. It was an incredibly tight fit that required a black belt in origami to overcome.

Get through all of that and these things were ripe for hotting up, with go-fast bits from the likes of Yoshimura and café racer panels from firms such as Dunstall.

My K2 ended up with an 812 Yoshi kit and Dunstall seat/tailpiece and I thought muggins was king of the kids. It felt terrifyingly fast at the time, though I now own half a dozen machines that would blow it into the weeds.

Some decades later I bought a restored a K1 from TT Motorcycles in sunny Mornington and have religiously left the poor thing alone, other than ride it and change the oil…

Ultimate 750

Really the ultimate ‘get’ for a CB750 nut is the race

version used by the likes of the legendary Dick Mann at

Daytona. Dubbed the CR750 (or CB750R), it was a top-to-toe

revision of the street bike (above), though its

architecture was largely the same.

Using a host of lightweight components, the four machines produced 90-plus horses and weighed around 155kg.

Mann won the 1970 Daytona race from the still fearsome Triumph team, led by Gene Romero.

Production figures

Honda produced numerous variants of the single overhead

cam four over the years, from 1969 model year through to

1978.

They included the K-series, autos, plus the sporty and

modernised F series.

Here are their production numbers:

CB750K0 53,400 (7414 sandcast)

CB750K1 77,000

CB750K2 63,500

CB750K3 38,000

CB750K4 60,000

CB750K5 35,000

CB750K6 42,000

CB750K7 38,000

CB750K8 39,000

CB750F 15,000

CB750F1 44,000

CB750F2 25,000

CB750F3 18,400

CB750A 4100

CB750A1 2300

CB750A2 1700

Sandcast specialists

There is a dedicated online club for sandcast owners – see it here.

World Motorcycles in the USA is a well-established sandcast restoration specialist.

Worth reading

The 1970 Two Wheels magazine

road test of the CB750-Four

Honda's heritage

piece on the CB750

The Honda Story

Published by Haynes (above) and written by Ian

Falloon

ISBN 1 85960 966 X

Good/bad

T160

Good

Quick

Stylish

Good handling

Not so good

Not as robust as the Honda

CB750-Four

Good

Lots of presence

Smart packaging

Strong mechanicals

Not so good

Handling is ordinary

Additional pics by Wikimedia, Mecum

SPECS: 1971 Honda CB750-Four K1

ENGINE

Type: Air-cooled, four-stroke SOHC, two-valve four

Capacity: 736cc

Bore x stroke: 61mm x 63mm

Compression ratio: 9.0:1

Engine timing: points and condenser

Carburettors: 4 x 28mm Keihin

PERFORMANCE

Claimed maximum power: 50kW at 8000rpm

Claimed maximum torque: 60Nm at 7000rpm

TRANSMISSION

Type: Five speed

Final drive: Chain

Clutch: Wet, multiplate

CHASSIS AND RUNNING GEAR

Frame: Steel twin cradle

Front suspension: Telescopic fork, no adjustment

Rear suspension: Twin shocks, preload adjustment

Front brakes: Single 296mm disc with single-piston caliper

Rear brake: 179mm drum

Tyres: 3.25-19, 4.00-18

DIMENSIONS AND CAPACITIES

Claimed dry weight: 226kg

Seat height: 800mm

Ground clearance: 160mm

Wheelbase: 1453mm

Fuel capacity: 18.2 litres (K2 tank on the bike shown)

OTHER STUFF

Production numbers: approx. 77,000

SPECS: 1975 Triumph T160

ENGINE

Type: Air-cooled, four-stroke pushrod, two-valve triple

Capacity: 741cc

Bore x stroke: 67mm x 70.5mm

Compression ratio: 9.5:1

Engine timing: points and condenser

Carburettors: 3 x 27mm Amal Concentric

PERFORMANCE

Claimed maximum power: 45kW at 7250rpm

Claimed maximum torque: NA

TRANSMISSION

Type: Five speed

Final drive: Chain

Clutch: Dry, multiplate

CHASSIS AND RUNNING GEAR

Frame: Steel, single downtube

Front suspension: 35mm fork, non-adjustable

Rear suspension: Twin Girling shocks with adjustable

preload

Front brakes: 254mm disc with single-piston Lockheed

caliper

Rear brake: 254mm disc with single-piston Lockheed caliper

Tyres: 4.10-19, 410-19 (bike shown runs a narrower front)

DIMENSIONS AND CAPACITIES

Claimed dry weight: 228kg

Seat height: 794mm

Ground clearance: 165mm

Wheelbase: 1473mm

Fuel capacity: 14 litres

OTHER STUFF

Production numbers: approx. 7000

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact