Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

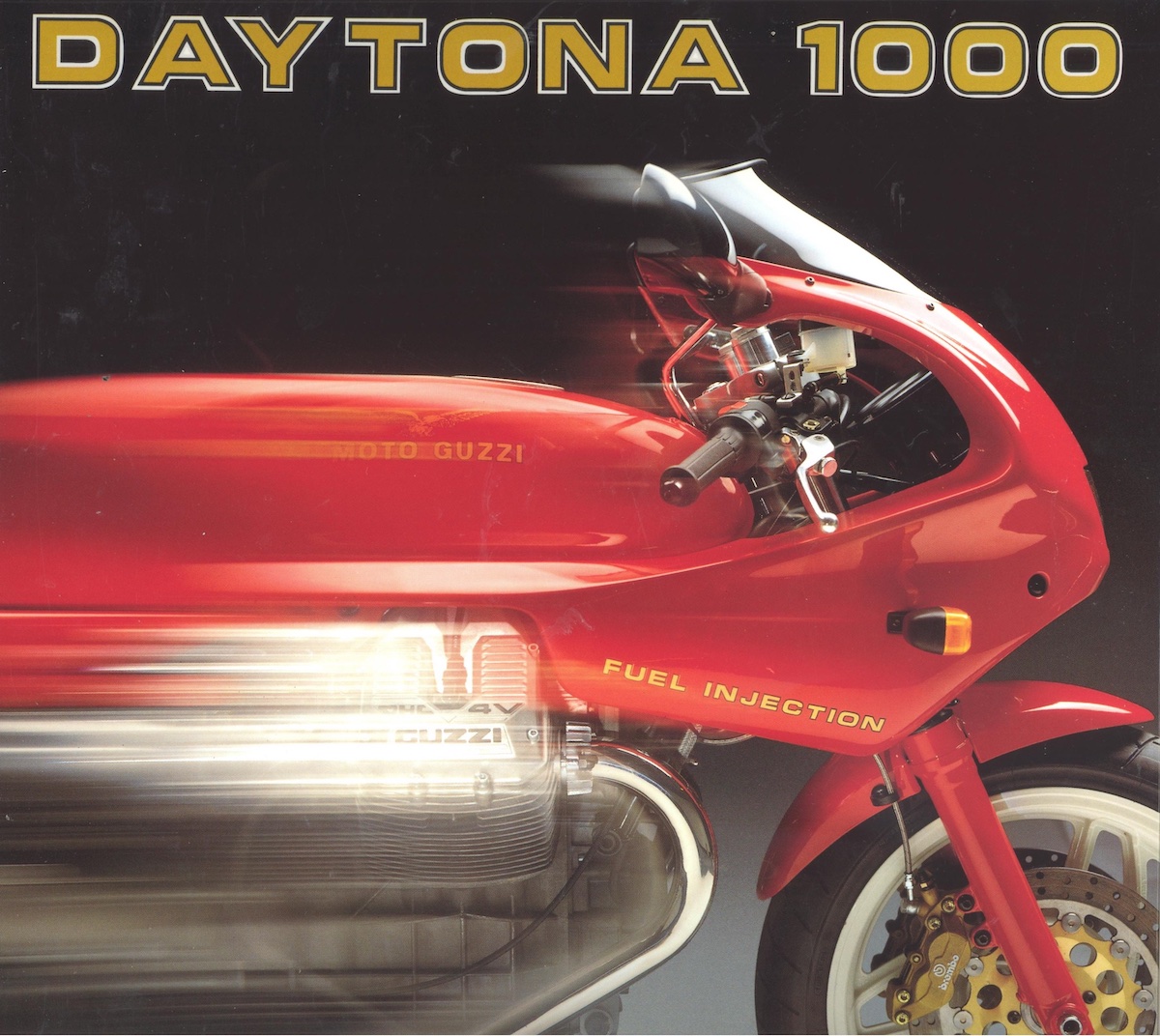

Future collectible – Moto Guzzi Daytona 1000

by Guy ‘Guido’ Allen, November 2020

Doctor's Orders

When racing really did influence the breed

This has to be one of the more peculiar stories in the annals of motorcycle racing, which is saying something. Moto Guzzi’s sexy Daytona 1000 (above) would never have happened if it weren’t for the strange passions of a USA Dentist, namely Dr John Wittner.

You see the good Doc didn’t do what you’d expect of dentists, which is take up golf and/or buy a Porsche. My dentist has named a wing on his yacht (which apparently has a mini golf course on the upper deck) after my family, but this one was a totally different kettle of fish.

Dr John (as he became known world wide) went motorcycle racing and, for reasons known only to himself, chose what may have been the least suitable brand on the planet to do it with: Moto Guzzi. (That's Dr John above at left, with rider Doug Brauneck – pic by Phil Masters, via Moto Guzzi.)

Sure Guzzi had raced before and even produced sports models, but the reality is the transverse V-twin shaft drive platform was far better suited to GT and touring bikes than sports models. You could hustle them along pretty quickly on the open road, but race tracks? Nup.

As it turned out Dr John was pretty quick as a rider, and

showed a talent for endurance events, but his bike

development skills were probably even stronger. Eventually

he saw the sense of bringing in some riding talent. In

1987 that took the shape of Doug Brauneck, an A-grader

with a good local reputation, who rewarded the team with

an AMA Battle of Twins championship in 1987. Yep, on a

Guzzi.

This quote from a Classic Racer magazine interview in 1987, sums up the man’s enthusiasm: “For a man who had been on a diet of 20-hour working days for five weeks, John Wittner sounded pretty chirpy. 'I feel like the luckiest guy on earth,' said the 41-year-old dentist from Dowingtown, Pennsylvania. 'I haven't got a penny, but there's nothing else I'd rather do than work with Moto Guzzi racing motorcycles.’”

That 1987 title-winning machine ran two-valve heads, as

per usual Guzzi practice. The good Doctor’s work had

caught the factory’s attention some years back and, by

1987, it was providing technical support. By 1987, it was

looking at adpating the four-valve heads designed by

Umberto Todero to the race bike for a tilt at the 1988

season. Sadly, it proved to be less reliable and didn't

enjoy quite the same level of success. Neverthless,

versions of the concept were raced into the mid-1990s in

the USA and UK.

Move on to the Milan show of 1989 and Guzzi shows off a Daytona developed in consultation with Wittner. It takes until 1992 for the bike to appear and the result was a rude shock to Guzzisti – it looked like nothing else the factory had produced.

Much of the thinking in the race bikes had transferred across, minus some of the more exotic materials, such as the extensive use of magnesium. The frame was new, as was the parallelogram shaft drive.

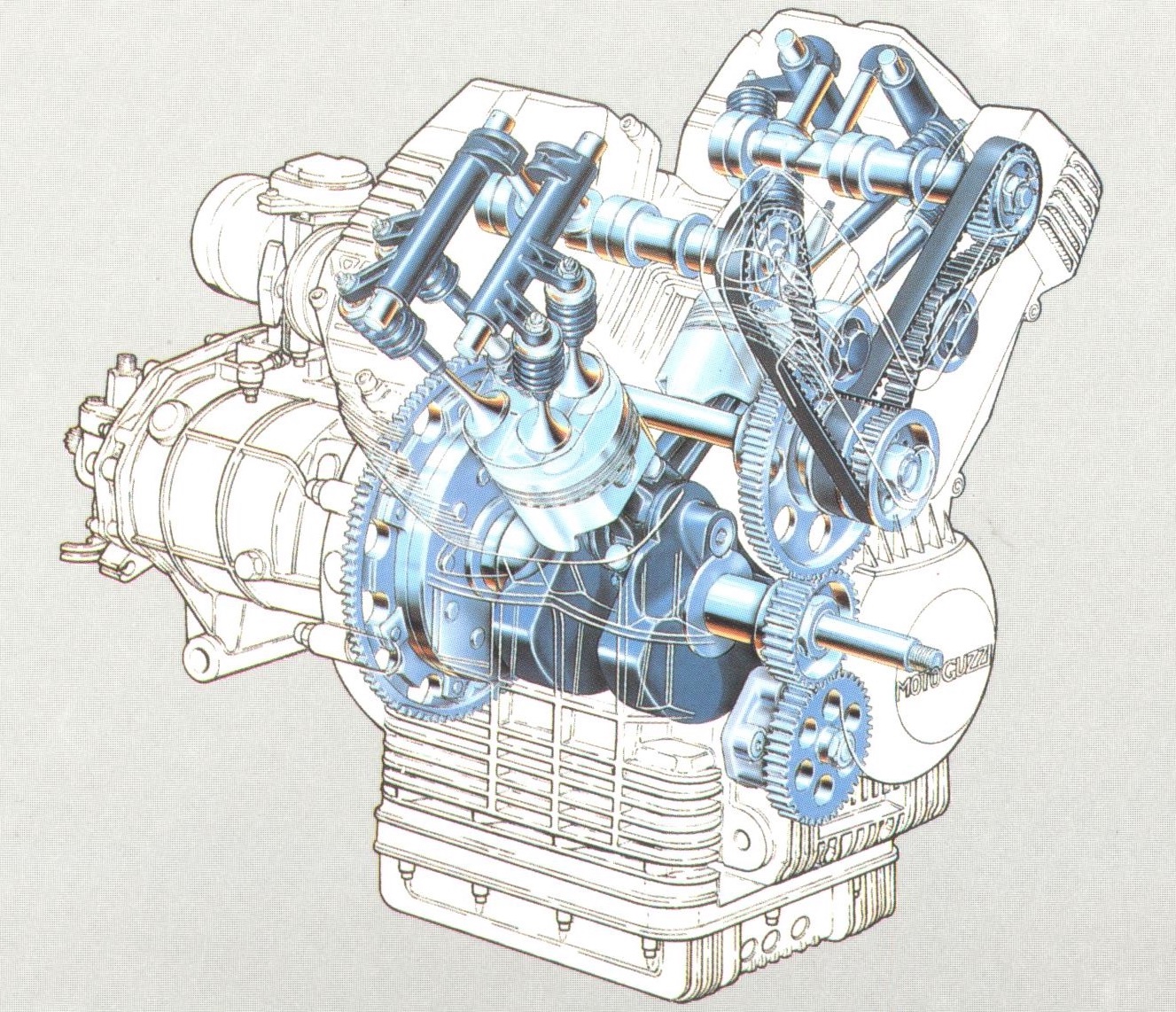

The real centerpiece was the powerplant. Called an overhead cam design by the factory, it was strictly speaking a high cam design using short pushrods to operate the rockers. The top end was driven by a relatively complex set of belts and gears and was fed by fuel injection.

Urge was a claimed 102hp, making it easily the most powerful Guzzi to date. Despite that it wasn’t terribly peaky, though it didn’t have quite the rich vein of mid-range offered by the later 1100 Sport.

Perhaps the biggest shock was the initial sticker price – an eye-watering Au$23,000 (US$15,500, GB£11,500). This was at a time when the just-released Honda Fireblade of the same year was priced at Au$12,700 (US$8600, GB£6400). The Daytona’s price did eventually wind back 15 per cent to around to Au$20k, but it was never mistaken for a cheap motorcycle and, as a result, few were sold.

That said, if you were a Guzzi nut, this was the ultimate aspirational model. Dr John had helped put the brand up in lights across the world and any red-blooded Guzzisti would have cheerfully sold their offspring to own one.

For the money, you did get a lot of premium gear, such as four-spot Brembo brakes up front (at a time when they were far less common than they are now) and WP suspension on the rear.

It was actually a damned good ride. The performance may not have been record-breaking, but it was still a seriously quick motorcycle with more than enough urge to land you in the clink. Acceleration was lively, as the four-valve engine was much more willing to spin up than its two-valve predecessors, though the fuelling from the Weber-Marelli injection wasn’t as smooth as it could be. It was a powerplant that rewarded spirited riding and was least at home pussy-footing through traffic around town.

The five-speed transmission shifted well, though the clutch was pretty heavy. Meanwhile the new shaft design, though worryingly noisy at times, did succeed in removing the usual strong rise and fall on the throttle.

Suspension was a real highlight on this machine. It was sporty and offered excellent feel, while remaining compliant and surprisingly comfortable. Overall the ride position was sports with a long reach, but by no means the most extreme position out there.

Steering was slow by sport bike standards – the equivalent Fireblade felt like a toy by comparison – and it responded best to an assertive tip-in. Once in the turn, it was rock steady and very reassuring. As a ride, so long as you didn’t mind the slowish steering, it was an absolute joy.

Downsides? Maintenance is more demanding than what your typical Guzzi owner might normally expect. Shaft drive universal joints are a wearing part and should be checked about 30-40,000km on hard-used examples. Cam belts also need periodic changing and the gears checked for wear. Oil pumps on very early examples also need to be watched.

Also, the gearbox oil needs relatively frequent replacement. In many respects this was the direct opposite experience of traditional Guzzi owners, whose maintenance concerns were minimal.

That wouldn’t stop me from owning one. If you walk in

with your eyes open and accept you’re getting into

something fairly exotic, there should be no surprises. In

reality, it's no more demanding than something like a

Ducati 916.

(Ed's note, 2024: we have bought one and love it.)

There was, perhaps inevitably, also a limited edition of

100 called the Racing, which predated the RS. In

Australia, this was priced at a massive 50 per cent

premium, or around Au$34,000 (US$23,000, GB£17,000). The

upgrades were significant, including a lift in

compression, different conrods and cams plus EFI tune. The

suspension and brakes were also upgraded.

If you lived in the UK, you might also have had the

opportunity to buy one of 20 1994 Dr John replicas. These

were fitted with the 'B' performance kit, painted black

and sported a Dr John graphic on the tail.

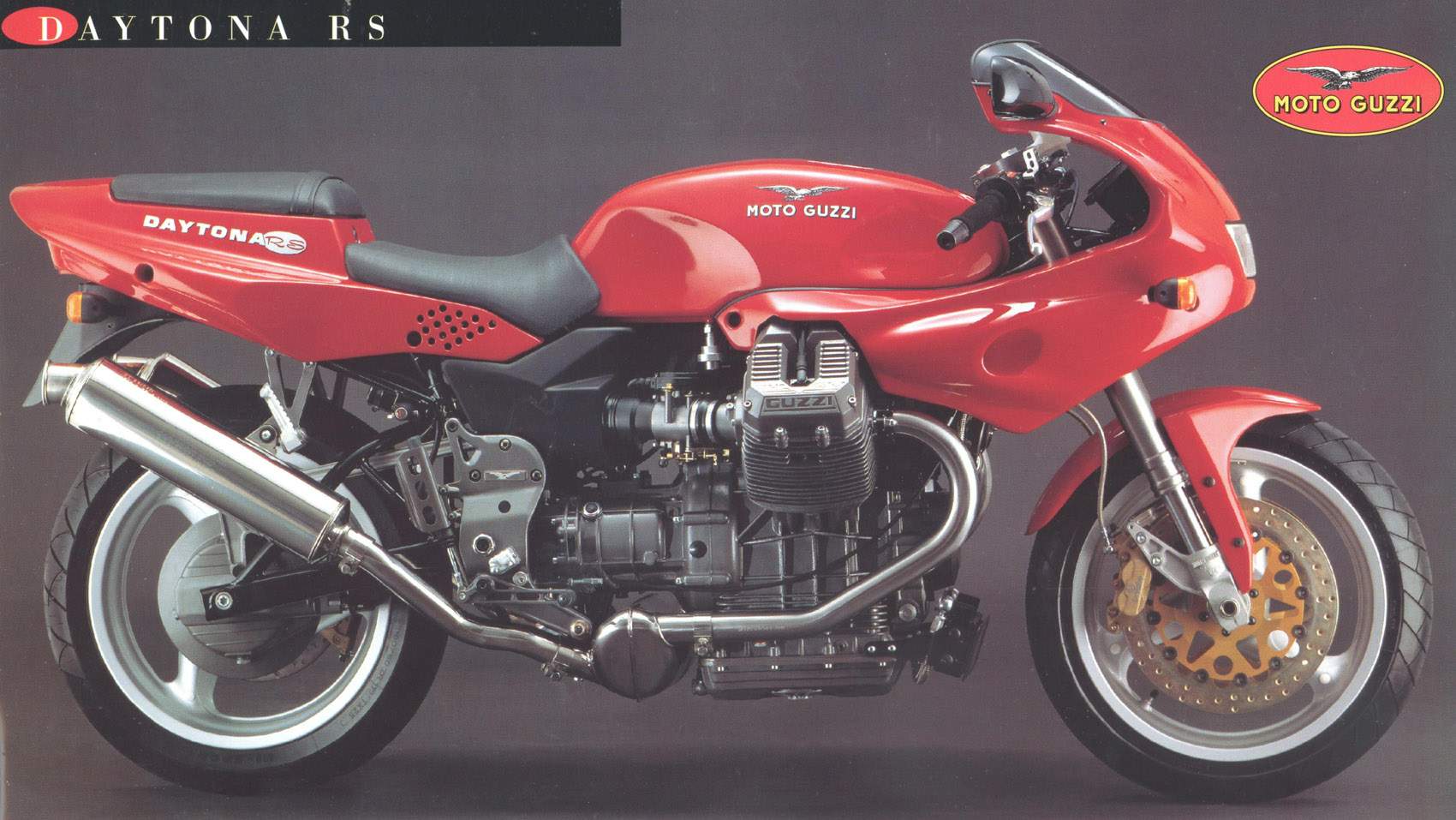

In 1994 we saw the switch-over to the Daytona RS. This

attended to some of the issues on the first model

and had a little more horsepower at a claimed 107. It also

ran 17-inch wheels at both ends, instead of the original

17/18 front/rear combo.

There’s no doubt in my mind all four variants are

slipping into collector territory, which can’t be argued

for most Guzzis.

So, is it worth the trouble? Yep. This qualifies as

Italian exotica and the chances of you going anywhere and

finding another one parked next to yours are slim in the

extreme. Looked after, they also happen to be a fun ride.

***

Best Alternative

Without question the best alternative to the Daytona is also a Guzzi that's very similar in appearance – namely the Sport 1100, circa 1996-2000. Retaining styling similar to the Daytona, it went for an 1100 two-valve powerplant, initially in carburetor and then injected form.

As a package, it was better sorted and developed. In

reality it was a better ride than its more exotic cousin,

with similar performance, but a little more mid-range. As

a used buy, it's significantly less expensive.

(Note: The version shown is a final limited edition

Corsa, of which 200 were made in 1998.)

***

Recent sale

Iconic Bike

Auctions in the USA sold a well-presented example

showing just 923 miles (1485km) on the odo in May 2023 for

Au$24,800 (US$16,000, GB£12,700).

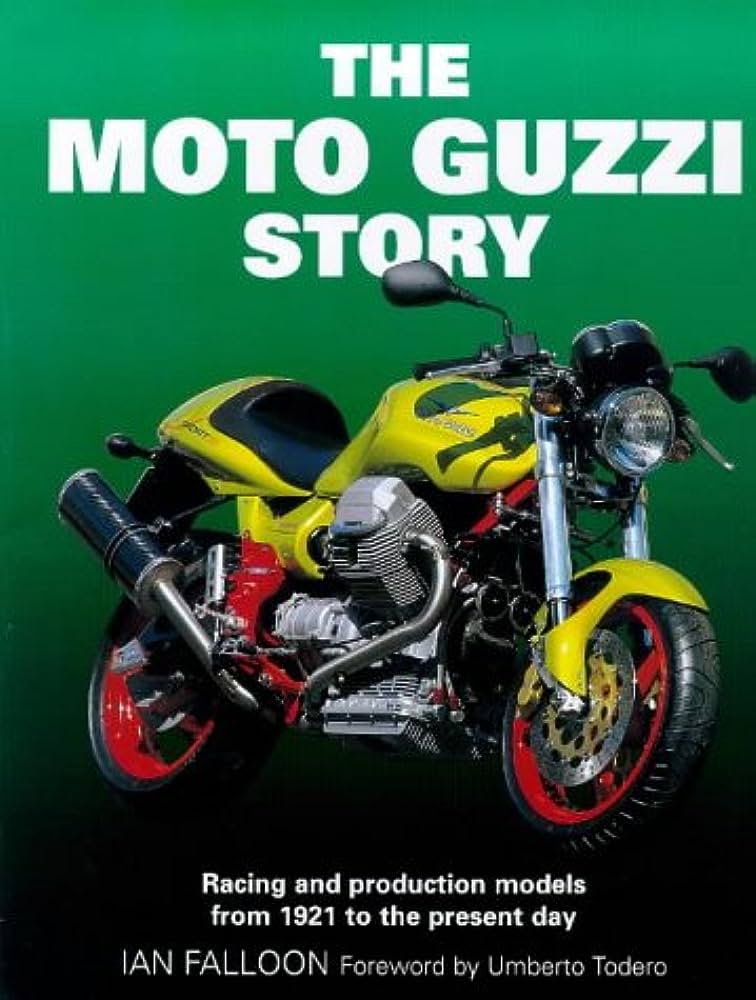

Further reading

See Ian Falloon's

history of the development of the Daytona at MC News.

See the bikesales story on buying 1990s classics

The Moto Guzzi Story, by Ian Falloon and published

by Haynes, has a chapter on Dr John and the Daytona. It

has a level of detail you'll find nowhere else.

Also see The Complete Book of Moto Guzzi, by the

same author.

Production

1991 – 1

1992 – 486

1993 – 283

1994 –155

1995 – 100

Total – 1025

SPECS:

Moto Guzzi Daytona 1000 and Daytona RS

ENGINE:

TYPE: Air-cooled, four-valves-per-cylinder, 90-degree

V-twin

CAPACITY: 992cc

BORE & STROKE: 90 x 78mm

COMPRESSION RATIO: 10.5:1

FUEL SYSTEM: Weber-Marelli fuel injection

TRANSMISSION:

TYPE: Five-speed, constant-mesh,

FINAL DRIVE: Parallelogram shaft

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR:

FRAME TYPE: Steel trellis

FRONT SUSPENSION: 40mm USD Marzocchi

REAR SUSPENSION: WP Monoshock

FRONT BRAKE: 320mm discs with four-piston Brembo calipers

REAR BRAKE: 260/283mm disc with 2-piston caliper

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES:

DRY WEIGHT: 223kg

FUEL CAPACITY: 23L

WHEELS & TYRES:

FRONT: 17-inch cast alloy with 120/70ZR17 radial

REAR: 18-inch cast alloy with 160/60ZR18 radial, 17-inch

with 160/60 on the RS

PERFORMANCE:

POWER: 102/107hp (76/80kW) at 8500rpm

TORQUE: 86/88Nm (64/65lb-ft) at 6600rpm

OTHER STUFF:

PRICE WHEN NEW: Au$23,000 plus ORC

For

Rarity

Fun to ride

Fabulous Sunday treat

Against

Price

Not built for big distances

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact