Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Super Nova

Profile: Triumph T300 Super III

(by Guy ‘Guido’ Allen, pics by Nathan Jacobs, Oct 2021)

Triumph's bright yellow Super III was the corporate flagship back in the nineties, though these days it's largely forgotten

Triumph's recent announcement that it is developing a new dirt bike range was about a lot more than just the motorcycles. It was confirmation that, some three decades after the brand's rebirth, it had every intention of comprehensively shaking off its niche player persona.

For some of us, it doesn't seem that long ago when annual production numbers were tiny, and the entire range was essentially a gaggle of variants based on a single platform. And 25 years ago, if you wanted the el primo selection from the Triumph catalogue, you bought a 1994-96 Daytona Super III.

Triumph at this stage was big on its modular concept of design and construction. It had one piston size, which by using two different strokes in three and four-cylinder configurations, gave them a 750 and 900 triple plus a one-litre and 1200 four. From there, they could derive all sorts of variants in different states of tune.

For a small maker (which it was, despite the massive investment), this method had the appeal of allowing them to build a respectable-looking catalogue with the minimum inventory of parts. Over time, it was the long-stroke triples (the 900s) that really gained cultural traction.

In those early days leading up to the mid-1990s, Triumph came across primarily as an engineering company. It was head-down and bum-up building things, while showing only a passing interest in the peripheral stuff like marketing. And it sure as hell wasn’t going to waste time and energy on damned fool things like racing. At least that was the impression it gave.

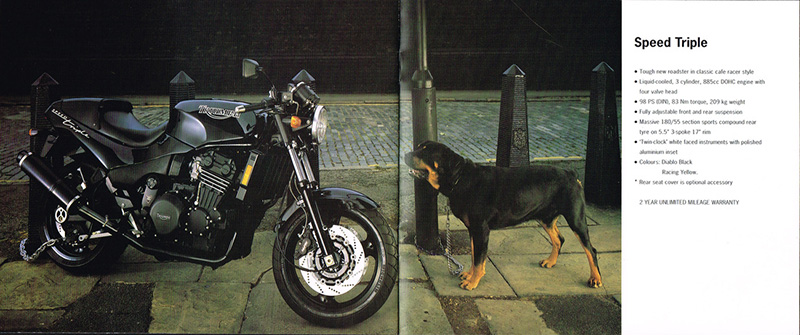

Nevertheless, it came out with some striking machines, such as the Speed Triple (above) – a modern classic, if ever there was one.

Another, much more rare, variant of the time is the Daytona Super III. It wasn’t the biggest, fastest and most powerful bike in the range – that place was occupied by the similarly high-strung 147hp (110kW) Daytona 1200 – but it was nevertheless the flagship at a hefty price premium. When a Daytona 1200 could be had for Au$18,500 (plus ORC), a Super III cost Au$21,000 (US$15,700, GB£11,400).

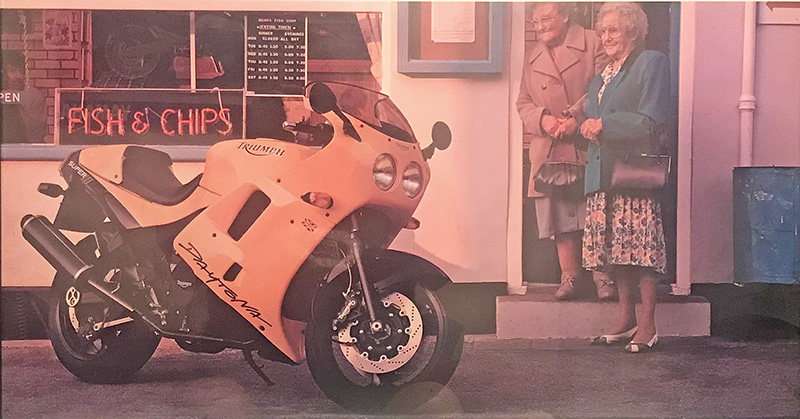

Unveiled in 1993 for the 1994 model year, it was available only in the marque’s blinding yellow. Its chief claim to fame was the powerplant had been tweaked in consultation with famous automotive tuning house Cosworth, to produce around 115 horses (85kW) at 9500rpm versus the standard 98 (72kW) at 9000 for a Daytona 900 (below).

Relative torque figures were 89Nm at 8500rpm for the Super III and 83Nm at a more relaxed 6500 for the 900.

The lift in performance was achieved through a higher compression ratio (12:1 versus 10.6:1), different profile cams and altered ignition curve.

Dressed up in unique badging, it came dripping with carbon-fibre (front guard, chain guard, fairing infill panels, muffler wraps) plus a set of six-piston front brake calipers made exclusively for Triumph by Alcon. Those same calipers could be bought as an accessory for other Daytona models. All up, it claimed to be two kilos lighter than a Daytona nine, at 211 dry (245kg wet).

As a ride, they were never cutting edge. They are relatively tall and can feel a little heavy, particularly when the giant 25 litre fuel tank is full. Plus, you have a long reach to the handlebars. So they suit medium height to tall people best.

The performance is enough to be entertaining if not mind-blowing and handling errs on the side of conservative. Really, they always were an exclusive sports-tourer and perform admirably in that role. The fairing provides excellent coverage, while the suspension soaks up the bumps well.

Gearshifting is a little on the heavy side, but dead accurate. They take a long time to properly run in – over 10,000km.

Braking from those six-spotters up front is truly exceptional and ahead of its time.

Servicing is normal for a current motorcycle and overall they are very robust. There are one or two people who specialise in them. Parts availability is mixed (good for service items, less-so for bits unique to this model) and the pricing is about what you might expect for the equivalent Japanese bike.

These days they are very thin on the ground. That’s because they were produced in low numbers – just 805 were made. Only tiny batches were originally imported into Australia. We're maybe talking as many as 20 examples. However a handful have since been privately imported, particularly from the USA where they've been typically undervalued. In any case, you're unlikely to ever see a herd of them parked together anywhere in the world.

This model is just becoming old enough to start making it on to the collector radar, but as of October 2021 were still some way from being in high demand. The oldest of them are now 27 years old, which means they can be put on club plates in WA and Vic in Australia, and are only a few years away for the remaining states.

What's to like? They're an unusual and very capable sports-tourer with a great name attached. That will do for a start, won't it?

Good

Nicely made

Exclusive

Peak Triumph UK revival

Not so good

Expensive when new

More sports-tourer than sports

Triumph's brochure and poster shots of the day were typically quirky.

SPECS

Triumph Super III 1994-96

ENGINE:

TYPE: Liquid-cooled, four-valves-per-cylinder, inline

triple

CAPACITY: 885cc

BORE & STROKE: 76 x 65mm

COMPRESSION RATIO: 12.0:1

FUEL SYSTEM: 3 x 36mm Mikuni CV flatslide carburettors

TRANSMISSION:

TYPE: Six-speed, constant-mesh,

FINAL DRIVE: Chain

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR:

FRAME TYPE: Steel with an Egli-style spine

FRONT SUSPENSION: Telescopic fork, 43mm, spring &

damper adjustment

REAR SUSPENSION: Monoshock, spring & damper adjustment

FRONT BRAKE: 310mm disc with six-piston Alcon calipers

REAR BRAKE: 255mm disc with two-piston caliper

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES:

DRY/WET WEIGHT: 211/245kg

SEAT HEIGHT: 790mm

WHEELBASE: 1490mm

FUEL CAPACITY: 25lt

TYRES:

FRONT: 120/70-ZR17

REAR: 180/55-ZR17

PERFORMANCE:

POWER: 85kW @ 9500rpm

TORQUE: 89Nm @ 8500rpm

OTHER STUFF:

NEW PRICE $21,000 plus on-road costs

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact