Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

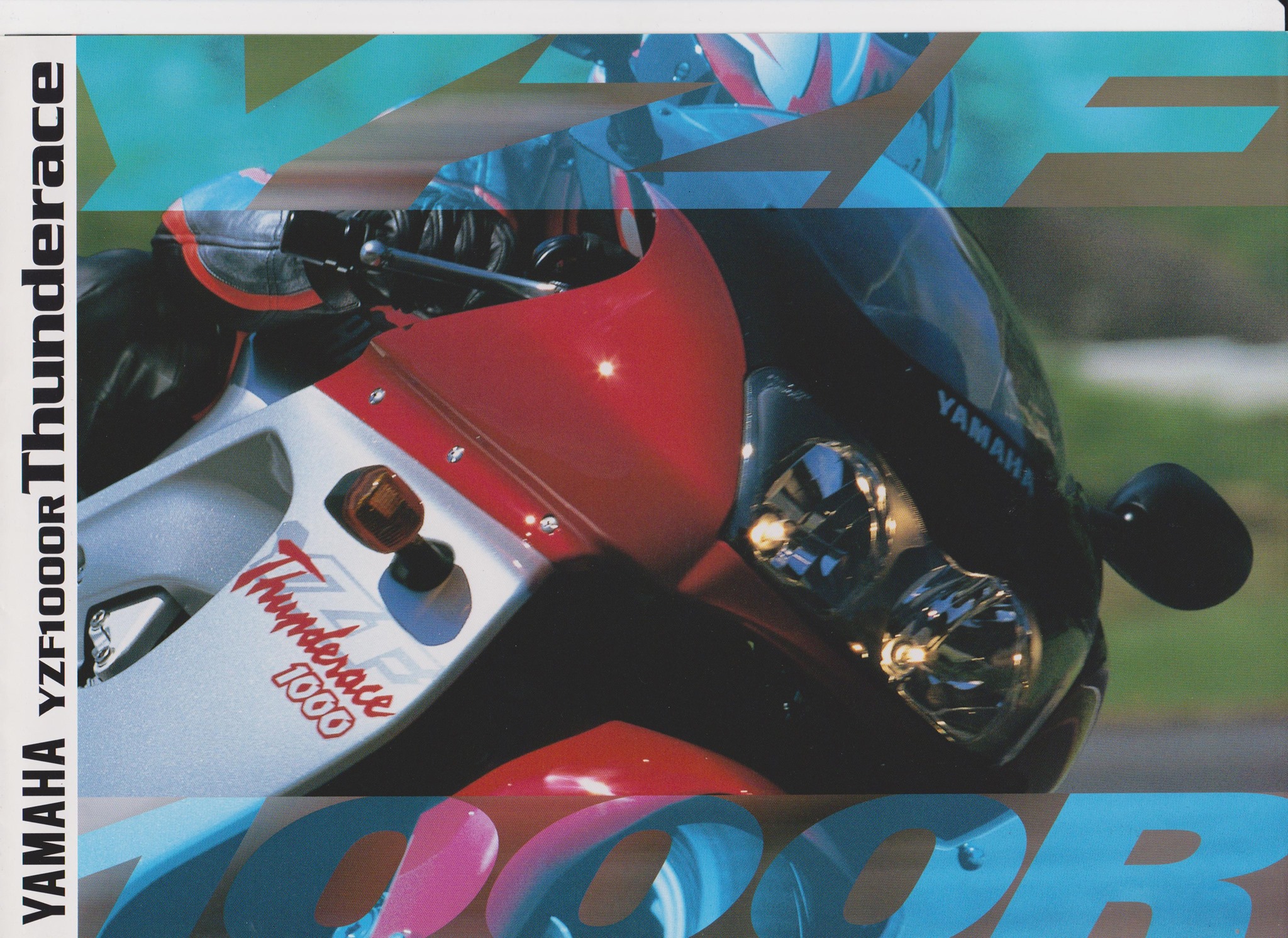

Future collectible – Yamaha ThunderAce YZF1000R

(September 2020)

Days of Thunder

by Guy ‘Guido’ Allen

Yamaha’s deliberate divergence from a hard-edged sports bike platform produced a great bike, but cost it dearly in the showroom

Back in 1996, just over two decades ago, the motorcycle showroom was a very different place. For sports riders, the 750 class was where the real action was – a phenomenon led by the world superbike championship, which had a 750cc capacity limit for four-cylinder machines. They were combating 1000cc twins – aka Ducatis. Honda and Suzuki were about to launch their own litre class sports V-twins, but that’s a story for another day.

Really, any four-pot sports motorcycle over 750 was a bit of an orphan in competition terms. Production racing was dwindling (the Castrol Six-Hour had ended a decade before) while the grand prix scene was still running 500cc two-strokes. Sure, there was endurance racing, but that had minimal traction in the mind of the public.

It was into this environment that Yamaha launched its successor to the successful decade-old FZR1000 series, the YZF1000R ThunderAce. Its competition was the likes of Honda’s lithe CBR900RR Fireblade, Suzuki’s GSX-R1100 (which by this stage was developing into a middle-aged sports-tourer) and Kawasaki’s very quick ZX-9R.

Triumph had recently re-emerged on the market, but the likes of its Daytona series (900, 1000 and 1200 in Australia) were very much sports tourers.

Yamaha wanted to re-assert itself in the sports bike litre class and, really, Honda had been the benchmark with its ultra-light and ultra-responsive Fireblade, launched four years earlier. However, the historical resources on Yamaha’s own global website reveal there was some internal conflict over how this would be achieved.

There was a real philosophical debate going on within the

company over whether they should follow the fast and

flighty Fireblade racer path, or take a more

rider-friendly road approach. This for a model that was an

interim offering between the FZR1000 and the upcoming (and

spectacular) new-generation R1.

Ken Nemoto, writing for Yamaha, reported: “‘While we were still developing the YZF1000R, the CBR900RR had amazed users with its handling, and it was selling very well,’ recalls Jiro Izaki (a member of Yamaha’s Road Testing Unit, 2nd Project Engineering Division at the time). He was in charge of track testing for the YZF1000R back then. ‘It really was a good bike. The feeling of lightness and the stability of its handling was shocking, even to us,’ he admits. Izaki went on to explain to us in detail how Yamaha proceeded to develop its own concepts for the style of handling they sought, regardless of what its rivals were doing.

“He told us that there was considerable debate within Yamaha at the time concerning whether or not they should pursue the same strategy as the CBR900RR that had become the category leader. There were even some members on the Yamaha testing team who were entranced by the bike. However, a consensus was reached among the testing team that, by their perceptions and standards, the handling of the CBR900RR was simply too ‘Spartan’.”

Now this is a rare insight into how major makers go about developing the concept and reality for a new model. Izaki went on to reveal that philosophically the team agreed they wanted to develop a motorcycle that focused on “what performance qualities are important for the way riders actually use their bike in touring and the like”. That represented a clear divergence from the Fireblade’s path, which was fairly uncompromising one-up performance.

The approach the team took was to take a YZF750R chassis and fit a litre engine out of the FZR series, then develop it from there. It sounds simple, but it’s a task that is anything but where you’re talking of integrating a complete and production-ready package.

And the end result? The ThunderAce. It had two major claims to fame: one was its light weight – 198kg dry, or where the Suzuki GSX-R1100 started out a decade before when it was just a bare bones endurance race replica. That on its own was remarkable for a motorcycle that still claimed ‘rider-friendly’ status.

Its second boast was a very respectable, if not earth-shattering, 145 horses tied to a very real claim of exceptional mid-range grunt.

To give you some idea of where that stood in the market, the 1997 Fireblade claimed 130 horses, 182kg dry weight and a 28mm shorter wheelbase.

If a motorcycle is to be solely judged by its sales, the ThunderAce (and, weirdly, its Thundercat 600 sibling - above) was a bit of a flop. It was a tough time to be selling premium motorcycles but the real issue was the gap in perceptions between Yamaha and its users. What Yamaha saw as a cutting-edge but still rider-friendly sports motorcycle, was perceived by reviewers and customers as a sports-tourer from day one.

So the debate that started in the engineering department some years before was being echoed out in the marketplace.

In fact the ThunderAce went on to be sold side-by-side with the much sharper R1 successor, and from 1998 accepted being typecast as the ‘softer’ alternative.

I’ve ridden a few of these things over the years and have a lot of time for them. However if at the time you were a potential Fireblade buyer, you would have got a bit of a shock if you first sat on a ’Blade and then the ThunderAce. The latter looked and felt like a much larger motorcycle, with a broad frame and tank and positively luxurious pillion accommodation when compared with the Honda. In the showroom, it looked and felt like a much bigger motorcycle – far more so than the mere 16 kilo weight gap would suggest.

Despite its generous curves, the ThunderAce turned out to be a seriously quick bit of gear. This was the first time Yamaha had fitted its in-house forged pistons to a motorcycle and the overall engine development was superb. Fast, responsive and very flexible, it was an absolute powerhouse. We were still running five valves per cylinder at this stage – three inlet and two exhaust per cylinder, as per the FZR series – which had become something of a corporate trademark.

Carburettors were still part of the package, though in this case a set of throttle-position sensors were used and integrated with the digital ignition.

The transmission was essentially accurate and faultless, though the decision to stick with five rather than six speeds was surprising. From a functional point of view, five did the job. But in a sports market, half the battle is bragging rights and, really, you needed six cogs.

Suspension at both ends was good gear – though a conventional rather than upside-down fork – with full adjustment.

Meanwhile the brakes were something new. Up front we got the four-spotter Monoblocs, which in various forms graced Yamahas for years and were very popular with modifiers as a retrofit on other models. The feel and power of these units was very good.

In practice, this was a fast and very capable motorcycle that was nimble enough to be fun on a set of curves. Though quite different in nature and feel to a Fireblade, in reality it was just as quick in most situations and a better day-to-day proposition, particularly if distances and maybe the occasional pillion were involved. Even now, I’d rate it as a fast and very usable package.

Really, the ThunderAce had only two years in the sun as the corporate hero bike before the R1 turned up on the scene. It lasted in the market all the way through to 2003, by which time sales had slowed to a trickle. Sadly, we never got to see the name used again. The model did develop some enthusiast user groups online, though these seem to have largely faded away over time.

These days there are usually a few on the market at any one time, varying hugely in quality. Prices seem to range from $3000 to around $7000.

From a collector point of view, these things are still some way off getting on the market’s radar. They’ll have some value in years to come as they are significant in the factory history as that transition model from FZR to R1 series.

For the time being, I’d regard one as having the potential to be a seriously capable ride that has some real curiosity value.

***

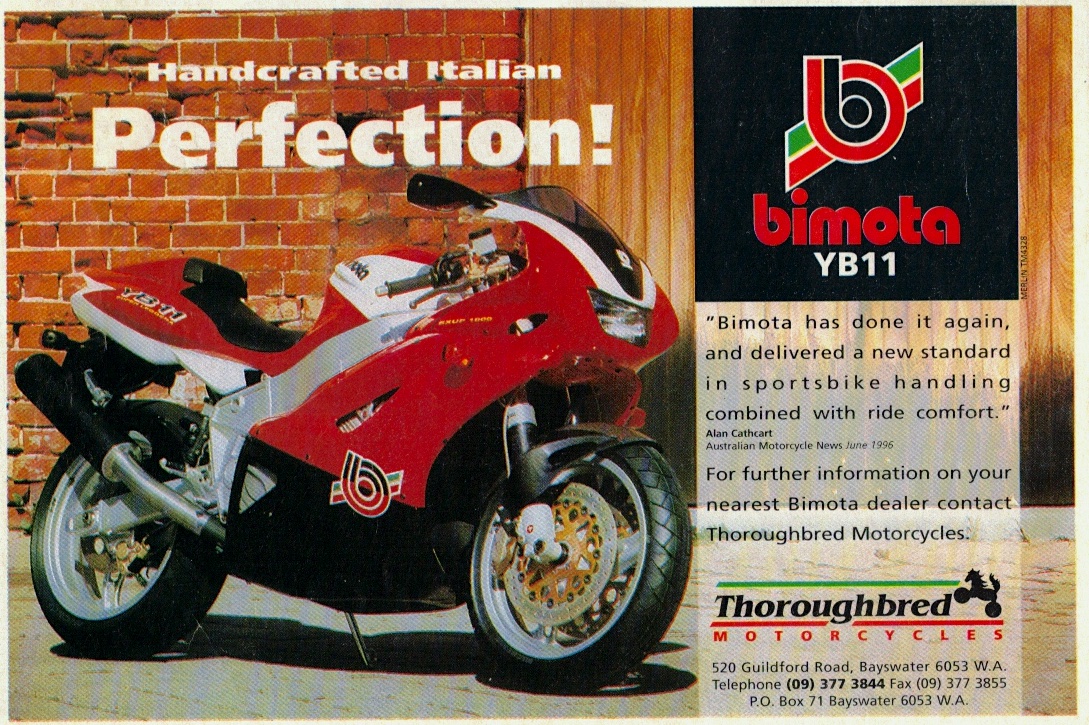

The Bimota connection

The final five-valve engine from the ThunderAce was

also the powerplant for Bimota's YB11 Superleggera. It was

one of the boutique firm's more successful models, with

some 600 made.

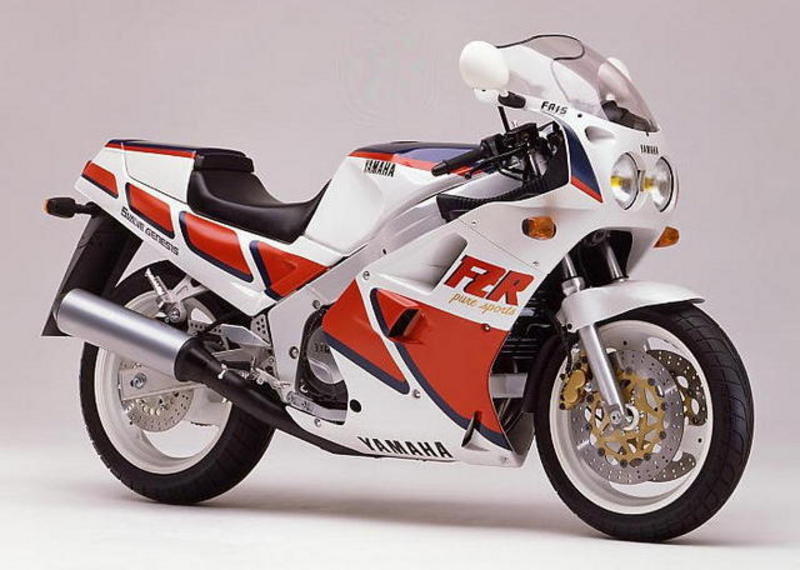

Yamaha’s sports hero transition

Yamaha’s FZR1000 series (1987 model above) was where this

story started, with the first model launched back in 1987.

That was also the year it dominated the last ever Castrol

6-Hour production race. (See the

story on our 6-Hour replica FZR1000.)

In 1996, the ThunderAce was launched and it remained in the market all the way through to 2003. It was essentially a hybrid of the YZF750R and FZR1000. (See our YZF750R feature.)

In 1998, Yamaha launched the R1 (below) – a clean sheet design - which for a while at least took over from Honda’s Fireblade as the class-leading litre class sports bike. (See our R1 feature.)

ThunderAce

Good

Fast

Handles well

Cheap

Not so good

Overshadowed by R1 & Fireblade

SPECS:

Yamaha YZF1000R ThunderAce (1996-2003)

ENGINE:

TYPE: Liquid-cooled, five-valves-per-cylinder, inline four

CAPACITY: 1002cc

BORE & STROKE: 75.5 x 56mm

COMPRESSION RATIO: 11.5:1

FUEL SYSTEM: Mikuni BDSR38 carburettors

TRANSMISSION:

TYPE: Five-speed, constant-mesh,

FINAL DRIVE: Chain

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR:

FRAME TYPE: Aluminium beam

FRONT SUSPENSION: Conventional 45mm telescopic fork, full

adjustment

REAR SUSPENSION: Monoshock, full adjustment

FRONT BRAKE: 2 x 298mm with 4-piston Monobloc calipers

REAR BRAKE: 245mm disc with 2-piston caliper

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES:

DRY WEIGHT: 198kg

SEAT HEIGHT: 795mm

WHEELBASE: 1433mm

FUEL CAPACITY: 19lt

WHEELS & TYRES:

FRONT: 20/70 ZR17

REAR: 180/55 ZR17

PERFORMANCE:

POWER: 107kW @ 10,000rpm

TORQUE: 110Nm 8500rpm

OTHER STUFF:

PRICE WHEN NEW: $16,000 PLUS ORC

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact