Motorcycle Investor mag

Future collectible - Kawasaki ZX-12R

(Guy 'Guido' Allen, April 2020)

King Kwaka

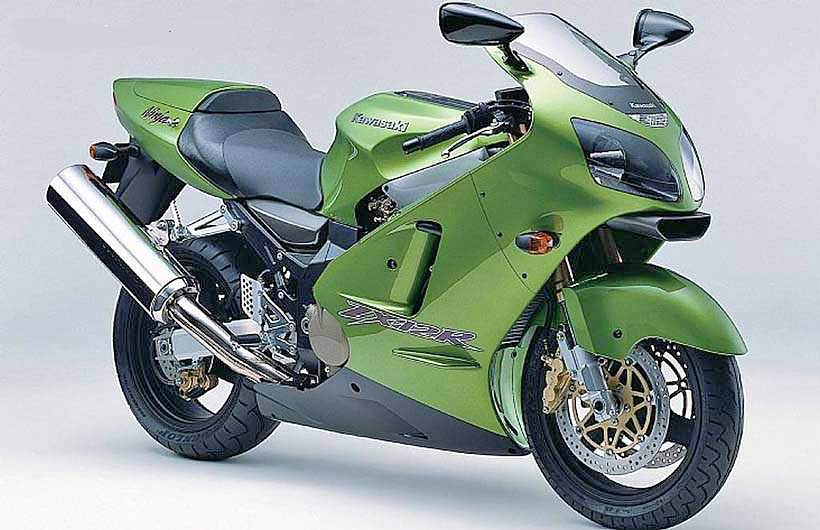

Kawasaki’s ZX-12R was meant to be the undisputed top performance dog, and it hit some speed humps along the way. It deserved better and is under-rated

Back at the turn of the century, which to some of you might seem when dinosaurs still roamed the earth, Kawasaki launched what it expected to be the king hit in the hyper sports tourer class. Up to then, there had been a couple of clear leaders.

First came the Honda Blackbird, launched in 1996, which

just edged out Kawasaki’s ZZ-R1100 as the reigning max

speed champ in production motorcycles, with a top end

nudging 290kph. Next say hello to Suzuki and its Hayabusa,

which took the number over 300kph (186mph), months before

the motorcycle industry as a whole adopted a 299kph agreed

top speed limit. Exactly how this was going to save anyone

or the reputation of the industry as a whole is up for

debate – it probably seemed like a good idea at the time.

Third off the grid was Kawasaki, at the very end of 1999 with its ZX-12R. This was meant to be the king hit for the class, and measured up that way in power terms. The Blackbird claimed 164hp (122kW) at the start of its career, the Hayabusa 175hp (130kW) and the Kawasaki nearer 190hp (141kW) with ram-air effect taken into account, while it managed 176 (one up on the Hayabusa) without ram-air.

One thing it lacked, strangely for this market, was a model-specific name. ‘Blackbird’ and ‘Hayabusa' were fantastic marketing tools. However the closest the ZX-12R came was ‘Ninja’, and that was almost generic and applied to a whole range of machines rather than this specific model.

At the time, as had been the case for decades, any now big performance bike announcement from Kawasaki made people really sit up and take notice. Since the launch of its Z1/Z900 series way back in 1972, it was established as a force to be reckoned with when it came to four-stroke performance bikes.

This machine took the whole hyper sports tourer gig off on a different tangent, which was definitely closer to the sports end of the scale. In appearance it was a giant sports bike rather than a hideously fast two-seater. Sure there was a pillion seat, but the accommodation out back was minimalist. Really, it looked more like a scaled-up ZX-7R.

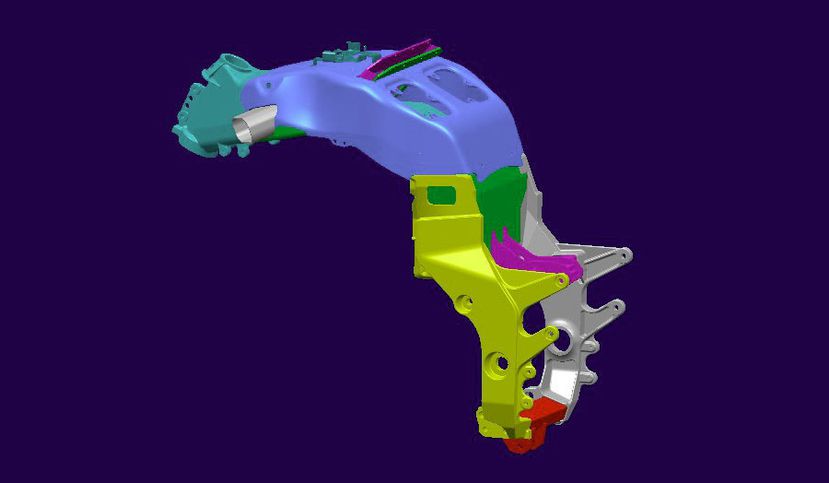

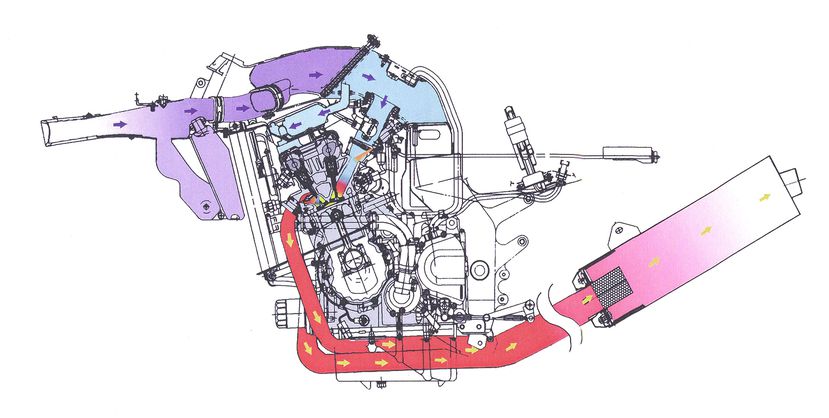

There was significant innovation in its design, most importantly in the frame. Rather than use the industry-standard twin aluminium beam, Kawasaki went for a giant monocoque arching over the engine from the steering head to the swingarm pivot, which incorporated the huge airbox and much of the ram-air plumbing. Fuel was held in an unusual tank that extended under the rider seat.

That was a major departure from conventional thinking and in some ways was reminiscent of some of the more imaginative (often privateer) endurance racing designs of the seventies and eighties. Kawasaki’s reasoning was this gave enormous strength, while keeping down the width. When you no longer had to wrap beams around the sides of the engine, you could keep the package narrow, which in turn aided aerodynamics.

Speaking of airflow, much was made of the factory’s use of wind-tunnel development, with the aid of the company’s aerospace division. “For example,” explained the factory blurb of the time, “the small canard-like winglets on either side of the fairing that look like downforce generators are in fact flow separators, preventing the turbulent air coming off the front wheel area from disturbing the laminar airflow along the upper section of the fairing. By physically separating laminar flow and turbulence, the fairing's coefficient of drag is greatly enhanced, enabling higher speeds to be achieved.”

Hanging off the unusual frame was a list of premium gear for its time. Up front there was a 43mm upside-down cartridge fork with a dizzying level of full adjustment, accompanied by a nitrogen-charged monoshock out back with similar facilities.

Braking was handled by twin 320mm rotors up front and six-piston Tokico calipers, with a relatively humble two-piston unit on a 230mm disc on the rear.

In keeping with the whole theme of narrow profile, the engine was as near as dammit to a clean-sheet design and some 11kg lighter than the equivalent ZZ-R1100 unit. The overall architecture was conventional enough – your typical liquid-cooled four-valve inline four.

However it ran the fuel-injected powerplant at a heady 12.2:1 compression and was leading the charge on the whole idea of ram-air. In short, this was one step back from forced induction (turbo, supercharger and the like) but used similar reasoning. As the bike gathered speed, fresh air was forced into the induction system at pressure, which in turn boosted its performance.

Explaining this feature was something that dogged the maker for years. The problem was that you wouldn’t get full horsepower when you tested the machine on a conventional dyno. The only way to get top numbers was to find a way to feed air to the scoops at the correct rate, which is much easier said than done – you might actually need a dyno in a wind tunnel!

The difference this made was significant. Kawasaki, with

the launch of the second-gen ZX-12R in 2002, released two

sets of performance numbers: 130kW in still air and 139

with ram-air. That’s a significant gap, equating to 12

horses. The claimed gap in the first-gen bikes was closer

to 11kW/15 horses

As a package, it was pretty short (40mm less in the wheelbase than a Hayabusa), tall and reasonably light at a claimed 210kg dry – or about 7kg lower than a Hayabusa. Typically for the period, there were no electronic rider aids. At this time BMW was still really the main proponent of fancy gadgets like ABS.

As a final statement, the ZX-12R was riding on big rubber – namely a 200 section on the rear, when its Suzuki rival wore a 190.

Feedback was nowhere near as clear cut as Kawasaki would have liked. It was certainly applauded for the cutting edge aspects of the design and the idea of creating a sporty sports tourer.

However there were some wrinkles in the launch. By far the biggest was a demo bike on loan to German mag Motorrad which punched a conrod through the crankcases during a high-speed run on an autobahn. As a result, Kawasaki pulled demo bikes from a few other mags across the globe for a safety check. Not a great start.

Number two on the list of ‘why us?’ was the timing of the

industry ‘gentleman’s’ agreement on a 299kph (186mph) top

speed. This allowed Suzuki to claim a 300-plus number and

prevented Kawasaki from doing the same just months later.

To make matters worse, when Cycle World magazine

retested the 2000 Hayabusa against the new Kawasaki, the

latter got mildly roasted. It seems Suzuki hadn’t been in

a hurry to bring in the required limiters…

In reality, a good first-gen Hayabusa could be relied on

to manage 305kph (189.5mph) top speed. Kawasaki, given the

industry speed restriction, made no claims. However given

its additional power and competitive 'narrow body'

aerodynamics, you would expect it was hoping for a little

better – a consistent 310kph-plus (192mph-plus), perhaps?

These things always come in threes, and number three on the list of launch glitches was the low-speed throttle response. It was generally reviewed as being a little jerky and perhaps in need of a little further development.

Those issues aside, the ZX-12R was deemed to be a spectacular performer, albeit better suited to larger folk who weren’t put off by the tallish seat and what was described as a slightly top-heavy demeanor.

Those prepared to grab the bike by the scruff were rewarded with what was in fact a very fast and very capable machine. It turned well, was well suspended and was in fact considerably sportier than its nearest rivals. There was no question it had a place in the market and was a very desirable bit of kit.

A second gen was launched in 2002, which Kawasaki claimed had something in the order of 140 alterations. On one hand we all enjoy a fresh approach to a design, but on the other did this say something unkind about the first model? In truth, this had as much to do with changing perceptions as it did performance.

The ZX-12R in its first incarnation came across as a fast and raw kind of motorcycle – particularly for this class. That can have huge appeal for the right people.

Whatever the reasoning, the alterations were extensive. Some, such as suspension, were upgrades that came with the march of progress. More telling was a modification of the crankshaft for a heavier flywheel effect to help smooth low-speed running, along with a revised EFI tune.

The chassis too was the subject of a lot of work. Kawasaki said it had built a little more flex into the frame – something that was topical at the time with GP bikes – while subtly altering the geometry. While the rake was steepened a little, the fork offset reduced and the wheelbase went up by 10mm.

Reviews of the day for this subtly restyled model were

kinder and there was little question the ZX had matured

into a very good piece of kit with a couple of the alleged

rough edges knocked off.

There was a third version from 2004, but the alterations

this time were relatively few, with upgrades to suspension

and brakes.

In the workshop: there are some popular myths regarding

servicing these bikes. In reality access is typical for

the period, which means you need to be patient to get to

spark plugs and valve-lash measurement. However they're no

worse than many contemporaries.

Shims are an under-bucket design, so changing them is a

big job. However feedback from owners suggest the

clearances tend to be pretty stable and access for

measuring them is no worse than for equivalent high-end

Japanese fours of the period.

After that rocky start in the market where do they now

sit? Long-term there are no consistent reliability issues

with them – owners seem to have the odd age-related issue,

but nothing that would put you off the model.

There are surprisingly few available and they seem like strong value for money. Prices are around $5000-9000, which strikes me as a hell of a lot of motorcycle for the money. You have to remember, launch glitches aside, these were seriously fast and cutting edge designs for their day. Even now, they’re a formidable performer.

After all the launch glitches, I’d still rate them pretty highly. The fact is that big performance Kawasakis have a history of doing okay in the longer term and I can't see a good example of this model getting a whole lot cheaper. I don’t think it matters a great deal which version you get, although a first-edition in green might command a little extra money.

Let’s see, there’s already a Blackbird and Hayabusa in

the shed – one of these might round out the set…

(Ed's note: we've since added one to the home fleet – see it here.)

Good

Fast

Innovative design

Kawasaki brand

Not so good

Mixed reviews

Not many out there

SPECS:

Kawasaki ZX-12R 2000 (ZX1200-A)

ENGINE:

TYPE: Liquid-cooled, four-valves-per-cylinder, inline four

CAPACITY: 1199cc

BORE & STROKE: 83 x 55.4mm

COMPRESSION RATIO: 12.2:1

FUEL SYSTEM: 46mm EFI

TRANSMISSION:

TYPE: Six-speed, constant-mesh,

FINAL DRIVE: Chain

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR:

FRAME TYPE: Monocoque aluminium

FRONT SUSPENSION: USD telescopic fork, 43mm, full

adjustment, 120mm travel

REAR SUSPENSION: Unitrak Monoshock, full adjustment ,

140mm travel

FRONT BRAKE: 320mm disc with six-piston Tokico calipers

REAR BRAKE: 230mm disc with two-piston caliper

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES:

DRY WEIGHT: 210kg

SEAT HEIGHT: 810mm

WHEELBASE: 1440mm

FUEL CAPACITY: 20lt

TYRES:

FRONT: 120/70-17

REAR: 200/50-17

PERFORMANCE:

POWER: 130kW @ 10,500rpm

static, up to 141kW with ram-air

TORQUE: 134Nm @ 7500rpm

OTHER STUFF:

PRICE NEW $19,390 plus ORC

***

Brochure pics

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact