Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe

to our free email news

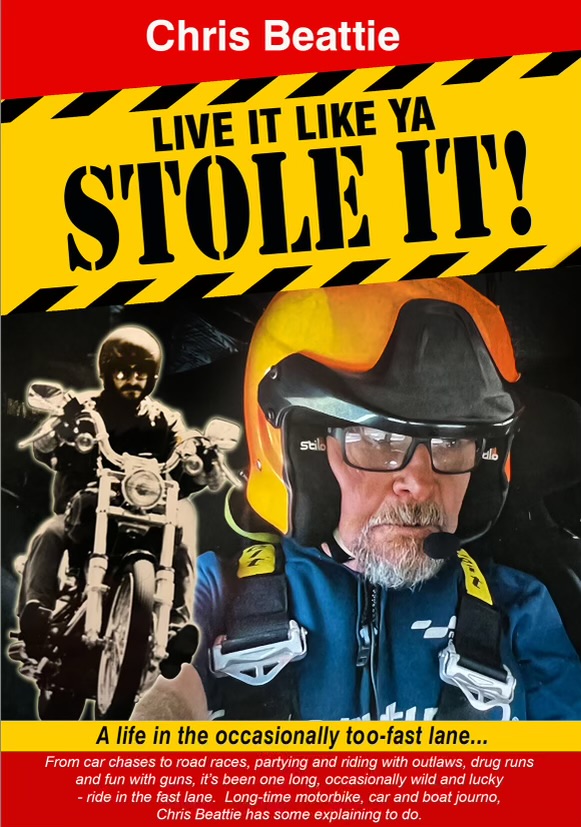

The Beattie Files: First love and a very warm ride

This was the precise

moment when I knew I was doomed to ride

motorcycles for the rest of my life. I was totally

absorbed in the experience

(Ed's

note: These are excerpts from young Beattie's book on

some of the more colourful incidents in an action-packed

life. See the end of the piece for more info.)

(Jan 2024, Chris Beattie)

.jpg)

“It’s an Ajay mate,

needs a bit of work, but most of it is there as far

as I can tell.”

It was covered in

dust, overspray and cobwebs and lay forlorn and

neglected in a dark corner of the panelbeater’s

workshop. To anyone else it might have looked like a

rusting relic beyond hope and mercy, but to me it

was a veritable jewel. I was 14 at the time and

needed a bike. Badly. I’d been bitten by the

motorcycle bug after my mate Bruce turned up one day

on a BSA 125 Bantam and let me take it for a flog

around the local dirt roads where we lived 40km

north of Auckland.

I’d been doing a bit

of hay-bailing over the summer to earn some pocket

money so I handed over the princely sum of $25, my

panelbeater mate even delivering the 1946 AJS 500

single to my home at no extra cost.

Which is where it sat for a couple of weeks as I

attempted to figure out what to actually do with it.

Of course, I understood that a motorcycle was

intended to be ridden. But in the case of my new

acquisition, it seemed that there was a bit more

work required to get it on the road than I first

anticipated. Both tyres were not only bald – they

were flat. The front wheel was minus a brake and

mudguard, there was no headlight, seat or generator

and no instruments to speak of.

The engine was actually intact, although missing an

exhaust system. And there was no primary drive cover

between the engine and gearbox, so the clutch and

drive chain were totally – and lethally -- exposed.

Plus, it had a rigid frame, so there was no rear

suspension to soften the many potholes and bumps

typical of local roads. There was definitely a bit

of work ahead.

Nevertheless, I was

totally absorbed by the task of getting the Ajay

going. Which for the first week or so involved

attempting to roll-start it down the side driveway

at the side of our property, which was perched on

the slope of a hill in farmland near the Pacific

coast. Each time it stubbornly and frustratingly

refused to utter even one hint of any internal

combustion from the battle-scared big single

cylinder engine. And of course, each and every

attempt at getting it going also required pushing it

back up

the dirt driveway to the garage behind our house. If

nothing else, it was great exercise, even if a

little unfulfilling for the most part.

But with some help

from a few older mates, including Bruce who owned

the Bantam and who had just started a mechanics

apprenticeship, we eventually figured out that a new

sparkplug might help. Next time down the driveway it

went bang … followed by more bangs. Given that the

previous two weeks’ efforts had produced no signs of

life, I was initially somewhat surprised to hear the

motor actually running. I was equally surprised to

note that the uncovered clutch, which was now

spinning mere millimetres from my bare foot,

appeared to be inoperable. The situation was highly

inconvenient given my progress down the driveway was

increasing rapidly. At the time we lived on a gravel

road, with deep drainage ditches on both sides, one

of which I was now approaching.

Another inconvenience

that I discovered a second or two before impact was

that we had somehow fitted the footbrake pedal over the

footrest so there was not enough travel to operate

the brake.

I was told later that

my somersault over the handlebars was quite

dramatic. The front wheel of the Ajay dug into the

clay bank directly opposite the driveway so the bike

stopped instantly – while I, plainly, didn’t.

Fortunately, the land on the other side of the road

was vacant, save for some scrub and a couple of

trees, so at least I had a pretty soft landing.

But I was so elated

that we at least now had the engine running, that I

barely noticed a couple of grazes and bruises. We

pushed the bike back up the driveway and

repositioned the foot brake pedal, as well as

adjusting the clutch cable. This time around Bruce

was in the saddle (we had crafted a seat by wrapping

a strip of shagpile carpet around the frame) as we

pushed her back down the drive. It fired first time

and as I stood by and watched, Bruce and the Ajay

disappeared up the road in a cloud of gravel dust

and engine smoke. Since I had yet to find an exhaust

system, it was also making a hell of a racket. I was

beyond excited and could hardly wait for Bruce’s

return.

He eventually

re-emerged out of the cloud and after making a

couple more adjustments, pronounced the bike ready

for my first ride. Plunging back down the driveway,

with hands on bars and heart in mouth, I dropped the

clutch and felt and heard the big thumper fire up. I

was on my way!

This was the precise

moment when I knew I was doomed to ride motorcycles

for the rest of my life. I was totally absorbed in

the experience as I rode all over the countryside,

including along a couple of the local beaches, until

the engine coughed and I switched over to the

reserve fuel tank. I turned for home and barely

stopped long enough to top up the tank before we

were off again.

The bike was totally illegal, with no lights,

registration, bald tyres and no hope of passing a

mandatory warrant of fitness. It didn’t even have a

sidestand, so I soon became adept at finding things

to lean it against, like shops, fences, powerpoles

and telephone boxes. I still didn’t have a licence,

but I couldn’t have cared less. That feeling of

freedom and power that only other motorcyclists can

understand had me in its spell. I was utterly

enthralled and remain so to this day, with each and

every ride reawakening something of that spellbound

14-year-old way back in 1970s New Zealand.

Over the following few

months I managed to round up an exhaust pipe here, a

headlight there and various other parts until the

old Ajay almost resembled a street-legal bike,

although I never did get around to registering it. I

had the occasional close shave with local cops, but

inevitably managed to make good my escape by

diverting across local paddocks or going for the

occasional ride along a beach or over sand dunes.

Which is how I also learned quite a bit about

riding, particularly over the pretty agricultural

local roads.

A small group of us

used to hit the road on weekends and venture a

little further afield, which is when I first had

contact with the Hells Angels, which had a chapter

on Auckland’s north shore, not far from home. One

member in particular, Will Dillon, a Maori guy with

a pirate-style metal hook for a hand, seemed to take

pity on me and actually helped me tidy up some

mechanical defects on the bike and offered the

occasional tip on how to deal with the cops whenever

I got caught.

Mixing with some of

the other members soon exposed me to a more adult

social circle – which resulted in a couple of other

major incidents detailed elsewhere in this book. But

I remember one in particular when a couple of

members offered to accompany me to the local police

station for my licence test.

Directly across the

road from the cop shop was the Wade River Hotel, a

pretty basic drinking establishment in the nearby

village of Silverdale, which was one of the first

pubs in New Zealand to bolt its furniture to the

floor and only serve plastic drinking vessels due to

the tendency of patrons to use them as weapons. The

floors were bare boards and all the windows were

barred. The only thing harder than the pub were the

crowds that drank there.

On this particular day

I rode on the back of Filthy Phil’s Triumph

Bonneville. The idea was that I’d use Filthy’s bike

for the licence test, since it was registered, but

instead of pulling up at the police station, we

parked in front of the hotel.

“I reckon ya need a

beer to steady ya nerves for the test,” advised

Phil. “You’ve got a few minutes to spare so no

fuckin’ stress mate,” he grinned, exposing two rows

of discoloured and broken teeth.

A calming ale seemed

fine by me because I was a little nervous about the

test given that the licencing cop was known to be a

stickler for the rulebook and didn’t particularly

like ‘bikies’.

After downing a couple

of beers, I realized that I was already a few

minutes late for the test so rushed out of the pub

and across the road, leaving Filthy to keep the

barmaid occupied.

“What the fuck do you

want?” sneered the tester. We’ll call him Constable

Bastard.

“I’m here to do my

licence,” I grinned.

“No you’re fucking

not,” was the curt reply as he continued to look

down at some official paperwork. “I saw you just

came out of the pub. As far as I’m concerned, if

you’re on the piss you’re not fit to take the test.

“And another thing, I

noticed you pulled up on the back of that sod

Filthy’s bike. Don’t bother coming back unless

you’re on your own. He’s fucking bad news mate. Do

yourself a favour and find another riding mate.”

Advice which I

ignored, of course. I was enjoying riding and

partying with Filthy, Will and a few of the other

local wild men, and despite being the youngest in

the group I was treated pretty well. They even

helped me work on the bike and taught me how to fix

the occasional breakdown, which was a fairly regular

occurrence on the Ajay. One thing English bikes

weren’t known for was reliability, so I never left

home without a good supply of spare parts and tools.

Eventually I got my

licence and a few months later I was offered an AJS

CSR 650 twin, a much more powerful bike that came

complete with registration. But, similar to the old

500, it still needed some work. For a start, it had

a large 6-volt car battery lashed to the seat with

ocky straps, had no mufflers and a slight knocking

noise which, memorably, became a broken crankshaft

as I was riding across the Auckland Harbour Bridge a

few weeks later.

On another occasion,

it blew a head gasket just as I was leaving the

mechanical workshop where I had started an engine

reconditioning apprenticeship. It wouldn’t have been

such a big deal except a portion of the head gasket

exited the engine and sliced through the fuel line.

Which in itself also wouldn’t have been such a big

deal – except that sparks from the engine then

ignited the escaping stream of fuel. All of a sudden

I was mounted on a two-wheeled flame thrower!

With traffic backing

up as flames spewed onto the road, I quickly

assessed my options. I knew the fuel tank wasn’t

bolted onto the frame, so leaned the bike on its

sidestand, lifted the tank off the bike – with the

fuel line still pouring out liquid flame -- and

thought for an instant about throwing it off a

nearby railway bridge onto the tracks below.

Luckily, there was a

motorcycle shop a block down the road. One of the

customers had seen what was going on and alerted the

manager, who came running up with a fire

extinguisher. He quickly snuffed out the fire and

left me to consider my next move. I could have left

the bike at work and arranged a lift home, but it

was a Friday night and there was a ride on over the

weekend that I didn’t want to miss.

I had a close look at

the engine and realized that I might just be able to

nurse it home. All I needed was another length of

fuel line.

I managed to get to

the bike shop just as the manager was locking up.

“Mate, thanks for

helping out back there,” I said. “Ummm, I’ve had a

look over the bike and I reckon I should be able to

get it home if I can just get another length of fuel

line,” I explained, laying the still smoking length

of plastic tube on the counter.

The manager prodded

the smouldering, blackened fuel line, before looking

at me and shaking his head.

“Mate, firstly,

there’s no fuckin’ way known I’m selling you another

fuel line. That fuckin’ thing will go up again as

sure as shit,” he said. “Wheel the fuckin’ thing

over here and I’ll look at it in the morning.”

Which is what I did.

Ultimately, the 650 and I spent a few happy months

together travelling all over the North Island,

before I eventually sold it to move to Australia.

But I still look back

fondly on the old 500. It was an angry, evil, ornery

mongrel of a bike that tried to kill me on more than

one occasion, and left me regularly stranded on the

side of the road. But a bit like a first romance, it

set a flame in my soul that no fire extinguisher

will ever put out.

(More to come...)

The excerpt is from Beattie's wild and woolly book. So far as we know it's had one brief print run and he's threatening to do another. Watch this space.

In the meantime he can be contacted by email.

More at The

Beattie Files home page

Travels with Guido columns here

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact