Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Future collectible - BMW K100-K1100

updated June 2020

by Guy 'Guido' Allen

The flat four society

When BMW decided to get out of air-cooled twins, the solution was one no-one predicted – least of all the customers!

This may go down as the most courageous decision ever made in BMW’s often entertaining motorcycle history. Not only was it branching out from the much-loved air-cooled (or ‘air-head’) boxer twins, but it was about to blow an estimated US$110 million (a fortune back around 1980) on a new factory that was to produce – wait for it – inline fours.

If you were a board member at the time, and were considering taking up drinking, this might have tipped you over the edge.

At the time we’re speaking of, there seemed to be something in the BMW DNA that made it genetically incapable of following a conventional path. So we’re not talking a familiar across-the-frame four. Oh no, we ended up with a unique configuration, with a litre-class injected DOHC four mounted along the frame and laid on its side.

How it ended up in this situation was a story in itself. A combination of tightening noise and emission regs, plus hot competition from liquid-cooled competitors, meant the writing was on the wall for the faithful air-head. It had to be replaced or at least augmented with something new.

We’re talking around 1977 when the company got serious about developing a new powerplant. It did in fact look very hard at the logical extension of the boxer twin – a boxer four – but Honda was already occupying that space with the Gold Wing, and BMW didn’t want to be seen as an imitator.

An inline four was hardly a new idea, and nor was having one along the frame. However the twist in the tail was the ‘flat’ mounting, with the crankshaft poking out one side of the frame and the head the other.

Of course the mid 1970s through to the mid 1980s was a phenomenal time in the motorcycle industry, when makers were pushing out a dazzling array of new designs and models – it seemed almost daily. In this environment, there was no guarantee that another maker wouldn’t have a go at something similar, particularly if they got wind of the idea.

The secrecy surrounding the new K-series was tight and the showing of the new models caused quite a ruckus back in late 1982.

Where did the engine come from? The story goes that the whole concept was first shown by the then young engineer Josef Fritzenwenger, using a PSA X-type engine, commonly used for mini-class front-wheel drive cars across Peugeot, Renault and Citroen. It was designed to be mounted at a relatively flat 72 degrees, not far off the 90 degrees proposed in the bike.

The whole idea certainly qualified as a point of distinction from the Japanese competitors and had the advantage that it was relatively easy to mesh with the company’s preferred shaft drive. And it got the green light.

BMW patented the general layout and got to work designing a fresh engine series. There were some challenges along the way, such as how do you fit a four-pot motor in lengthways and not end up with some monstrously long motorcycle, or one with an unacceptably short swingarm?

When the firm launched the series, there was plenty for the somewhat gobsmacked market to talk about. The weird engine location for a start, or perhaps the very early adoption (for a motorcycle) of fuel-injection – in this case a Bosch LE Jetronic, system adapted across from the car division.

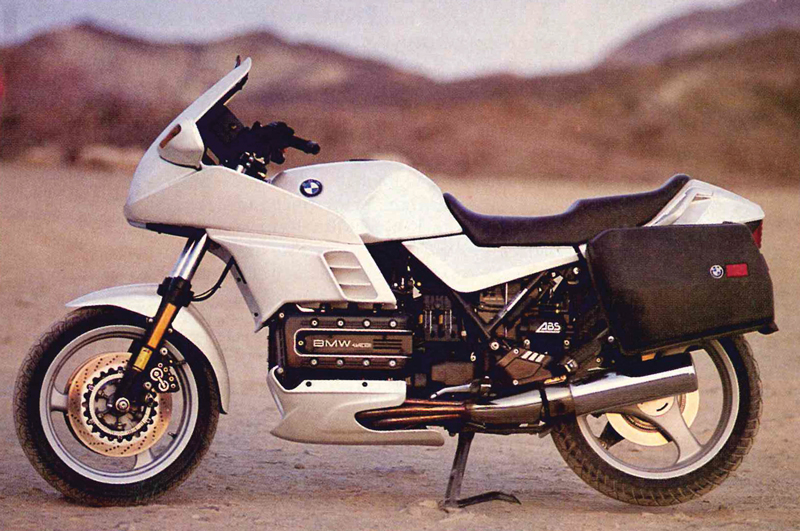

The chassis was a tubular space frame with the engine as a stressed component, while the rear end was a single-side swingarm. There were three key models early on: the naked K100 (above), K100RS sports tourer (top of page) and K100RT tourer (below). Of course there were more variants to follow.

Stats were good rather than headline-grabbing. Typically for BMW, the powerplants (liquid-cooled, undersquare, double-overhead cam with two valves per pot) were tuned for low and mid-range rather than spectacular top end. We’re talking a max whack of 90 horses (67kW) with something like 85 per cent of the max torque delivered by a modest 3500rpm. That lot was punting a 250kg (wet) bike.

Despite those modest numbers, it was actually quick enough. You’re talking a 220km/h top speed and a quarter mile time of 12.5sec for the RS.

Around the bike, there was plenty of BMW thinking: decent-sized fuel tank, sensible wheel and tyre sizes (no 16-inch fashion victims here!), a single-plate dry clutch (just like the old boxers) and of course that shaft drive. It was built as much for the long haul as any other duty.

Where the naked K looked unfinished and the RT tourer like a flying barn door, the RS carried on very much where its twin-cylinder predecessors left off. The fairing looked smart and offered a whole lot more protection than the rider might at first expect. When the rain gods decided to strike, you were pretty well covered from ankle to neck.

One thing that helped ‘make’ the RS (above) was the optional factory panniers – a rarity in the sports tourer class – that added hugely to the model’s versatility.

As a handling package, they erred on the side of conservative. Long and fairly heavy, they responded best to a planned approach to your cornering lines, rather than a last-second sports bike attack. Braking from the Brembos (two-piston calipers up front) was strong with decent feel for the day, while the suspension did a pretty decent job of keeping the plot together.

This wasn’t a super-sharp package, but in the days before the infestation of speed cameras, you could punt one along at a very respectable clip and achieve good point-to-point times.

They did suffer a few glitches. Early fuel fillers had an unpleasant habit of dumping water in the tank; And if you left one on the sidestand overnight, you were quite likely to be greeted with a very smoky start-up. Both issues were dealt with as the series progressed.

One disappointing aspect was the character of the engine, which droned rather than growled. For some, that could be a deal-breaker. I had a colleague who rode a demo RT, didn’t like it, and bought a Gold Wing instead.

An interim engine update saw a 16-valve head and Motronic fuel injection system introduced to the one-litre powerplant, for 1990-91. This saw service in the wild-looking K1 (see our K1 ownership story) and K100RS 16-valve (above).

It took almost a decade, but in 1992 for the 1993 model year, BMW finally launched a major upgrade across the series, with the main feature being the 16-valve head and the jump to an 1100.

The upgrades were numerous and worthy. The powerplant was smoother (though the buzz was still there!) more powerful (100 horses), the rear end now featured the articulated Paralever shaft, suspension was much-improved and the front brakes now boasted four-piston Brembo calipers. And it came in for a redesign that included fairing lowers. To my eye, this was by far the best-looking of the ‘flying brick’ BMWs.

As you might suspect, the improvements ran deeper than the bodywork. The 16-valve engine is far superior to the eight, with a truly impressive midrange. Suspension and brake response had both moved up a few notches (to be expected given the intervening decade!), while ABS had been added to the range. All up this made the 1100RS (above) a bike I would still rate as very capable piece of kit today. One surprising oversight was that BMW stuck with a five-speed transmission, when the engine was clearly capable of running a tall sixth gear.

Like its K100 predecessor, it was still very much pitched as a sports tourer and was never going to be mistaken for anything else.

Overall reliability of the K100/K1100 series is very good, with 100,000 being a very long way from worn out. Mileages of 300,000km-plus are surprisingly common for the engines.

Their mechanical Achilles heel is the combination of the main seal at the back of the engine, and the clutch. More often than not, a leaking seal will cause the clutch to slip. Replacing both (you might as well once you’re in there) involves dropping the shaft and the transmission, which is time-consuming and/or expensive. Once that’s done, however, it should be good for another couple of decades.

The Gen 1-2 ABS (with the giant black actuators) can throw up error codes which most often turn out to be false alarms.This can be quickly reset and the solution is readily found on the internet. Age can eventually get to them and, if they fail, it's sometimes financially sensible to simply remove it and replace the lines with readily-available non-ABS equivalents. At this stage in BMW's history, ABS was generally an option and so the conversion should have no impact on being able to register the bike.

These bikes were relatively expensive back in the day and the sales were not huge. The Bimmer faithful were still buying air-head twins, albeit in dwindling numbers, and the need for a replacement was finally answered with the release of the oil-head series in the 1995.

So far, they seem to have been largely overlooked as a potential classic. However they were a significant piece of the marque’s history and the RS, of all the bricks, is the one to have. An early K100 would appeal to some collectors as the first of a series, though a K1100 will be a better ride and holds some intrinsic value.

Your biggest issue will be finding one that hasn’t either been worn out or hacked up for another project. In the K100RS, look for the Motorsport colour scheme, with is a white with a subtle stripe.

How much? Prices vary wildly, but a good to excellent K100RS should fetch around Au$2500-4000 and equivalent K1100RS around $3500-6000.

Snag a well cared-for one and you just might be surprised at how capable it is.

***

What about the 1200?

We’ve dodged that one for the moment as it was effectively a complete redesign that really needs to be tackled as a separate topic.

Suffice it to say that it was far more powerful, had a totally different frame that helped evict the buzzing Ks were famous for, and was a formidable bit of kit. A story for another day…

Triple treats

Yes, BMW did produce a three-cylinder version of the Ks, effectively the same bike with the front cylinder lopped off.

There were three main versions: K75C (above) , K75S (below) and K75RT. The C had a mini handlebar fairing and a reputation for being a little flighty on the front end. That problem was addressed with a ‘fluidblock’ steering damper.

Meanwhile the S was a slightly more ‘together’ effort with a frame-mounted sports-tourer fairing unique to that model.

Finally there was the RT, a full tourer.

The triples ran a counterbalance system and tended to be smoother than the fours. Local sales numbers were very modest.

Further reading

The Complete Book of BMW Motorcycles

By Ian Falloon, published by Motorbooks.

SERIES RATINGS

Good

Capable & quick

Long-lasting

Relatively cheap

Not so good

Can be buzzy

Clutch repair is complex

SPECS:

BMW K100RS/K1100RS

ENGINE:

TYPE: Liquid-cooled, two/four-valves-per-cylinder, inline four

CAPACITY: 987/1092cc

BORE & STROKE: 67/70.5 x 70mm

COMPRESSION RATIO: 10.2/11:1

FUEL SYSTEM: Bosch Jetronic/Motronic fuel injection

TRANSMISSION:

TYPE: Five-speed, constant-mesh,

FINAL DRIVE: Single-side shaft/paralever

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR:

FRAME TYPE: Steel space frame with engine as stressed member

FRONT SUSPENSION: Conventional telescopic fork

REAR SUSPENSION: Monoshock

FRONT BRAKE: 285/305mm discs with two/four-piston Brembo calipers (ABS on K1100)

REAR BRAKE: 285mm disc with single-piston caliper

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES:

WET WEIGHT: 250/268kg

SEAT HEIGHT: 810mm

WHEELBASE: 1516mm

FUEL CAPACITY: 22lt

WHEELS & TYRES:

FRONT: cast alloy with 100/90 V18 or 170/70 ZR17

REAR: cast alloy with 130/90 V17 or 160/60 ZR18

PERFORMANCE:

POWER: 67/73kW (90/100hp)

@ 8250/7500rpm

TORQUE: 86/107Nm @ 6000/5500rpm

OTHER STUFF:

PRICE WHEN NEW: $7000/20,500 plus ORC

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact