Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Ducati's landmark Imola victory

(by

Ian Falloon, April 23, 2022)

Today marks the 50th anniversary of what many

regard as the true start of the Ducati legend

In Ducati folklore the 1972

Imola 200-mile race is a defining event. Before Imola

Ducati was a minor Italian motorcycle manufacturer of

esoteric four-stroke singles with strange valve gear,

but after Imola they could take on the worlds best and

comprehensively beat them. As Ducati’s great engineer

Fabio Taglioni said in 1974, “When we won at Imola we

won the market too.” It was the Imola victory that

ostensibly set the stage for Ducati’s subsequent

success.

Imola would never have

happened if Ducati hadn’t just introduced their 750cc

V-Twin, and this only came about through the 1969

company restructure. The decade of the 1960s had been

difficult for Ducati. A series of dubious business

ventures nearly strangled the company, and it would have

sunk into oblivion like many Italian motorcycle

manufacturers but for quasi government bailout every

year.

During 1969 the financial

situation was so precarious that Ducati was absorbed as

part of the EFIM (Ente Finanzaria per gli Industrie

Metalmeccaniche) group. At the end of 1969 new directors

were appointed and Ducati Meccanica was given a new

lease of life. Arnaldo Milvio was appointed Managing

Director, with Fredmano Spairani as Coordinating

Director, and they came to Ducati Meccanica with a fresh

approach. Somehow, they found the resources to develop

the new 750 Twin and instigate a racing program.

When the 750 was conceived

Fabio Taglioni was 49 years old. But the father of

desmodromic valve gear for motorcycles was virtually

unknown outside Italy, and Ducati was still a minor

motorcycle manufacturer in world terms. Despite the new

management, economic viability was essential, and

Taglioni was instructed to utilize as much carryover

technology from the existing range of singles as

possible.

A V-twin made sense as many

features of the existing overhead camshaft singles could

be incorporated, and Taglioni liked the idea of an

engine that was little wider than a single. Taglioni

chose a 90-degree V-twin layout, a carryover from the

V-four Apollo seven years earlier. In one of several

interviews I asked Taglioni why he chose the 90-degree

cylinder layout. Taglioni replied, “The 90-degree L-twin

provided perfect primary balance. The engine can be very

smooth, with only some high frequency secondary

imbalance, and with a narrow crankshaft there is

virtually no rocking couple. Also the twin can be narrow

so the engine can be kept low in the frame while

maintaining good ground clearance.”

Along with the development of

the 750 Taglioni was also working on a 500cc Grand Prix

twin. With a special frame by Colin Seeley Bruno

Spaggiari, and later Phil Read, campaigned this in

mainly Italian events during 1970 and 1971. Although the

twin struggled against the MV triples much was learnt

that would help when it came to the preparation of the

Imola machines in 1972. A 750cc version was also built,

Mike Hailwood testing this at Silverstone in July

1971.He qualified sixth fastest but decided not to ride

it as he felt it didn’t handle well enough.

With the announcement of the

Imola 200 “Daytona of Europe” to be held on April 23,

1972, Spairani instructed Taglioni to mount a full-scale

attempt at winning the race. With record prize money the

Imola 200 was to be one of the biggest race meetings

ever staged in Europe, and Imola was in Ducati’s back

yard, only a short skid down the autostrada from

Bologna. Spairani was determined to hire a top rider to

head a line-up of six entries. He approached Jarno

Saarinen, Renzo Pasolini, and Barry Sheene, Spairani

visiting Sheene at the end of February to secure the

deal. Although Sheene didn’t end up riding the Ducati

because they couldn’t agree to the fee, he was still

listed in the program riding number 18.

In early March Taglioni and a

group of leading Italian motorcycle engineers traveled

to Daytona for the 200-mile Formula 750 race. Taglioni

came back optimistic. While he found the speed of the

350 Yamahas devastating he knew they weren’t eligible to

race at Imola. With the Yamaha out of the equation

Taglioni looked at the rest of the competition. Mostly

four-stroke, he reasoned he could build a

better-balanced machine particularly suited to the Imola

circuit. He took ten production 750 frames and began

building a batch of Formula 750 racers. It was

originally intended to build ten machines for six

riders, but according to Taglioni in an interview in

1995 only six were officially certified, with one spare,

for four riders.

Right until the last minute

there was uncertainty as to who would ride the works

Ducatis. Ducati hadn’t mounted such a factory racing

effort since 1958 and all the top riders were skeptical,

none believing the Ducati twin would be competitive.

Already signed were Bruno Spaggiari (on number 9),

Ermanno Giuliano (45), Vic Camp’s rider Alan Dunscombe

(39), and Gilberto Parlotti (24), although he also

didn’t race.

Needing another top rider,

British distributor Vic Camp suggested Spairani approach

Paul Smart, then racing a Kawasaki H2-R for Team Hansen

in America. As there was no race in America that weekend

Paul’s wife Maggie accepted the invitation in his

absence and Smart initially wasn’t too impressed. But

Ducati was paying good money and after a Triumph ride

fell through, Smart was soon down in the program on

Ducati number 16, listed just ahead of his

brother-in-law Barry Sheene.

The first Imola race bike was

completed in time for a Modena test by Spaggiari on 6

April in preparation for the first official test session

on 19 April. Incredibly this was only four days before

the race and only five machines were available, Smart,

Dunscombe, and Giuliano riding them for the first time.

Smart had only just arrived from a race at Road Atlanta

and was initially unimpressed saying, “It was so long it

looked will it would never go around a corner, but after

riding it I found it deceptively fast. Ducati had

obviously put a lot of effort into it. It just felt slow

revving, like it fired every lamp post.”

All Smart found to criticize

were the street Dunlop K81 “TT100” tires, and extremely

high footpegs. After altering the footpegs Smart went

out again, breaking Agostini’s lap record on street

tires. Ducati was reluctant to change the tires, fearing

racing tires wouldn’t last 200 miles but Smart persuaded

Taglioni to procure some Dunlop KR83 and KR84 racing

tires.

Although the racing

desmodromic 750s looked surprisingly similar to the GT

and Sport, they were highly developed factory racers

sharing little with the production 750. Phil Schilling,

Cycle magazine's managing editor at the time, saw the

bikes in the Ducati race shop a few days before Imola.

He wrote, "The first thing I saw, the thing that

immediately dented my mind, was a center stand.

These factory racers were all

parked on center stands, stock center stands, which were

connected to stock frames, which joined standard front

forks and near-stock swingarms. And the production-line

frames held embarrassingly standard-looking engines.

Sure, there were special pieces: big Dell'Orto

carburetors, high-rise/low-rise megaphones, dual discs

in the front and single discs in the rear, oil coolers,

hydraulic steering dampers, and racing shocks. But where

were all the really trick parts? There weren't any."

Schilling’s observations were

as accurate as could be made at the time, but as with

all factory racing Ducatis there was more to the Imola

racers than met the eye. The frames may have started as

production Verlicchi items (with center and side stand

mounts and frame numbers) but were considerably modified

to accept the large fiberglass fuel tank and provide a

suitable racing riding position. The fiberglass fuel

tank included a large clear stripe as an instant fuel

gauge because the machines would require a fuel stop

during the 200-mile race.

The frames retained the

29-degree steering head angle but were narrowed at the

base of the fuel tank. The forks were machined leading

axle Marzocchi, providing around 100mm of travel, with

standard length (305mm) Ceriani shock absorbers.

Many 750 GT parts were

modified and adapted for the racer, such as the front

278mm Lockheed discs and the machined production 38mm

leading-axle Marzocchi fork. Unique to the racer was a

rear 230mm disc, and 18-inch WM3 Borrani wheels front

and rear. As there were only left side Lockheed calipers

in stock for the 750 GT, three left-side calipers were

adapted for the racers. After the test at Modena a

hydraulic steering damper was also installed, at least

on Smart and Spaggiari’s machines.

The engines may have

ostensibly looked standard but these were also special

race motors. Taglioni took early production 750

sand-cast engine cases rather than the production type

used at that time. These were heavier, but Taglioni

considered them stronger. Inside were re-routed oil

galleys, welded-up bosses for external oil cooler lines,

and cooling fins shaved to allow the right-hand exhausts

to fit more snugly.

The crankshaft incorporated

lighter solid billet con-rods with strengthening ribs

around both the little, and big-ends, higher ratio

straight-cut primary gears with a drilled clutch basket

and a close ratio five-speed gearbox. To reduce

reciprocating weight the flywheel and alternator were

removed and the pistons a Mondial higher compression

slipper type.

Also setting the racer apart

were desmodromic cylinder heads, the ports carefully

welded up, enlarged and finely polished to flow gases

through the 42 and 38mm valves. The desmodromic

camshafts providing a claimed 13mm of inlet valve lift,

the engine was safe to 9,200 rpm. The total loss points

ignition system featured twin spark plugs per cylinder,

the additional 10mm Lodge spark plug allowing ignition

advance to be cut back to 34 degrees before top dead

center.

After his experience with

electronic ignition failure on the 500 GP bikes during

1971 Taglioni wasn’t prepared to risk it at Imola.

Taglioni was also worried about heat build up and

installed an oil cooler in the front of the fairing

cooling oil to the cylinder heads, also mounting the

ignition condensers on the front frame down-tubes, away

from the heat of the engine.

With a pair of the new

generation Dell’Orto PHM 40mm concentric carburetors

without chokes, Taglioni claimed the power was 86

horsepower at 9200rpm, but the broad spread providing

with 64 horsepower at only 6000rpm.

In many respects the Imola

machines were designed for one race only. At that time

Imola was a very fast old style circuit around the hills

at the back of the old township, primarily on closed-off

public roads. As there was only one tight right hand

corner (the Aqua Minerale), the kickstart and kickstart

shaft were removed and a close fitting exhaust pipe

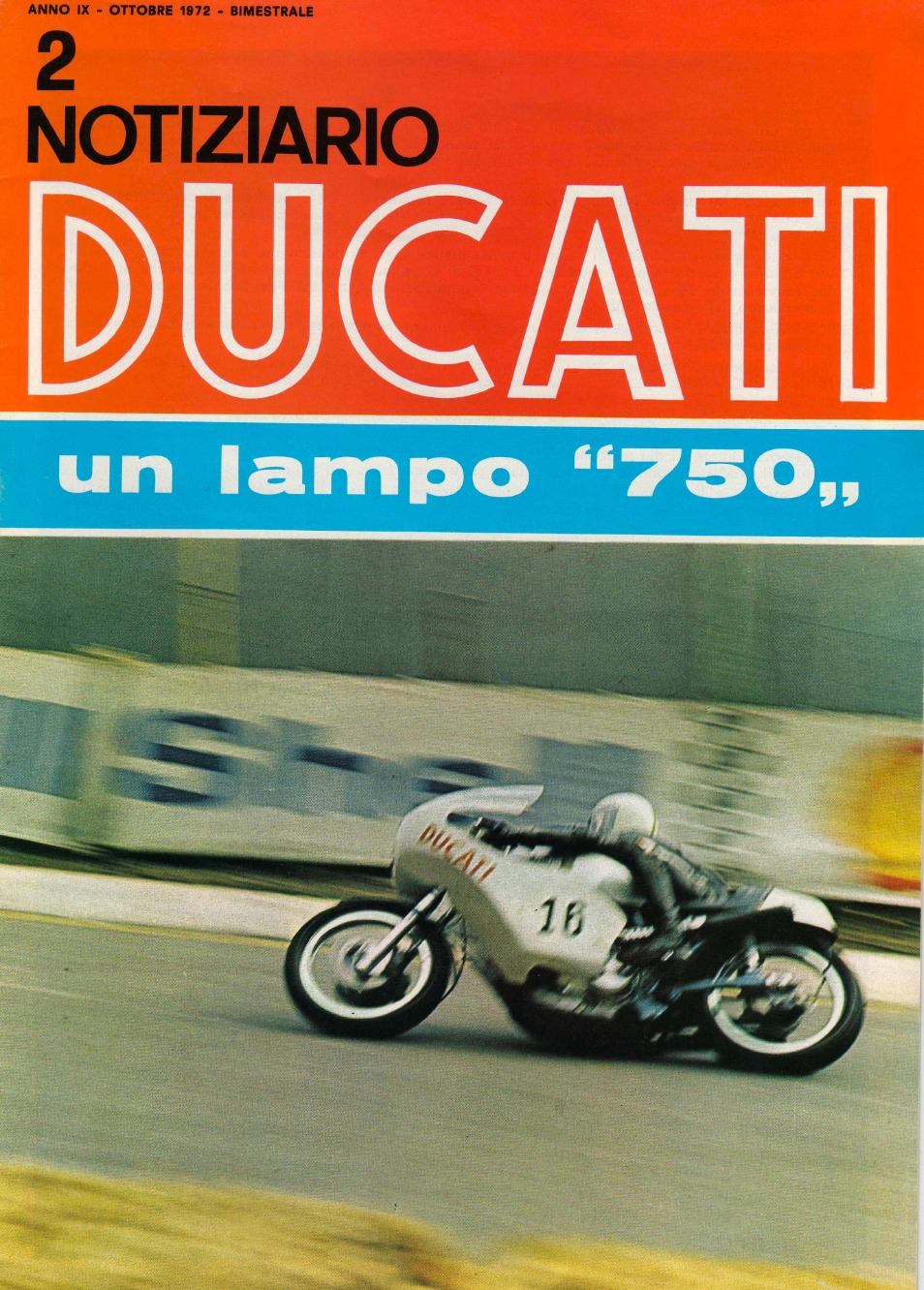

installed on the right.

The left pipe was high-rise

and as Imola was a high speed circuit the long 60-inch

wheelbase wasn’t considered detrimental. The dry weight

was 292 pounds, and despite the rather non-aerodynamic

fairing they were reputed to pull the tallest available

gearing, achieving around 169mph at the bottom of the

hill and through the full throttle Tamburello corner.

Seven bikes were taken to

Imola, in a specially constructed glass-sided

transporter, (2 #16, 2 #9, 2 #39, and #45) with

Spaggiari setting the fastest time in practice on the

Friday, and along with Smart was fastest again on the

Saturday. Ducati went into the race full of confidence,

with Spairani particularly convinced the Ducatis would

win. Before the race he told Smart and Spaggiari they

were going to be first and second, and they were to

share the prize money. They were not to dice for the

lead until the final five laps, and if Smart won he

would keep the bike.

On race day for the “200

Miglia Shell di Imola” at 3.1 mile Autodromo “Dino

Ferrari” Imola, 70,000 spectators crammed in to see who

would win the total prize money of Lire 35.000.000, at

that time a world-record. The entry list comprised one

of the most competitive fields ever in F750. Along with

four factory Ducatis, MV Agusta provided machines for

Giacomo Agostini and Alberto Pagani, and Moto Guzzi had

official entries for Guido Mandracci and Jack Findlay.

From England were the factory John Player Nortons of

Phil Read, Peter Williams, and Tony Rutter, the BSA of

John Cooper, and the Triumphs of Ray Pickrell and Tony

Jeffries.

And completing an impressive

array of factory machinery were the 750 Hondas of Bill

Smith, John Williams, Silvio Grassetti, and Luigi

Anelli, and the BMWs of Helmut Dahne and Hans-Otto

Butenuth. There were also strong contenders in

Daytona-winner Don Emde, Walter Villa, Ron Grant, and

the Kawasakis of Cliff Carr and Dave Simmonds. And in

addition to the factory teams and many of the world’s

top riders was an array of more than 70 journalists from

around the world, a number more appropriate for an auto

rather than motorcycle event. The winner was going to be

assured top publicity.

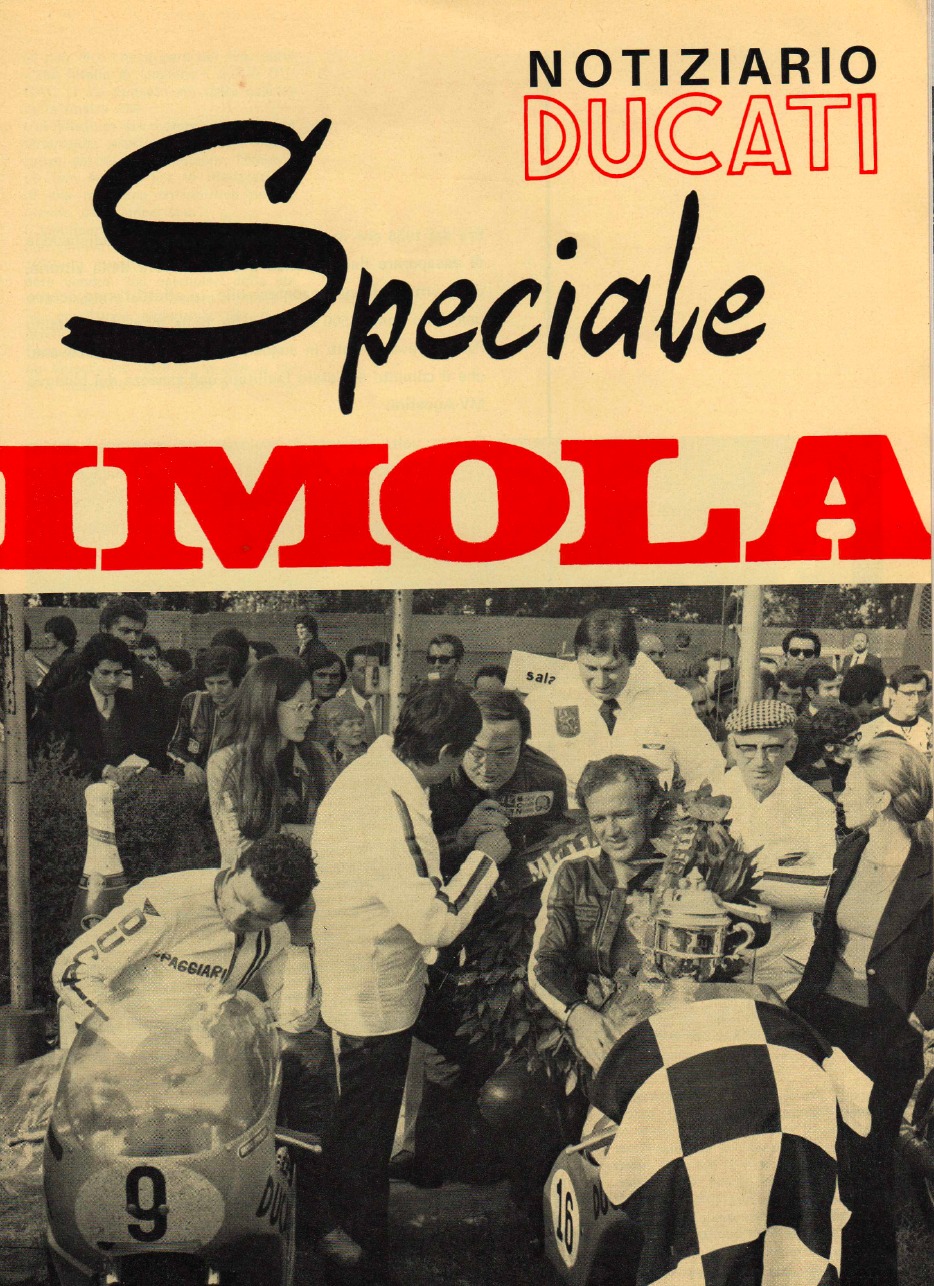

On race day the two silver

Ducatis followed Agostini for four laps before Smart

took the lead. Although he lost first gear early in the

race Smart wasn’t handicapped and comfortably held first

for most of the race. Agostini retired on lap 41 and

Spaggiari then overtook Smart on lap 56. The two Ducatis

circulated together, even pitting for fuel

simultaneously. Smart regained the lead two laps from

the end after Spaggiari ran wide at the Aqua Minerale.

Both very low on fuel and

misfiring, Smart crossed the line four seconds ahead of

Spaggiari who was now only running on one cylinder.

Smart’s race average was 97.8mph and he shared the

fastest lap of 100.1mph with Spaggiari and Agostini. It

was Smart’s 29th birthday and it was arguably the most

significant victory in his career. It was certainly a

pivotal victory in the history of Ducati. They had

proven to the world their desmodromic 750 could take on

all comers and win.

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact