Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Six Runner

Getting the 1981 Honda CBX1000 on the road

Bought

at auction, this old CBX six has had a colourful

life and proved to be a bit of a project to get

back on the road...

(Feb 2024, Guy 'Guido' Allen)

It all began with an

unreasonable urge to add a straight six to the motorcycle

shed and the model had been narrowed down to a CBX1000

Honda.

Why? Love the Benellis – or the idea of

them – but I didn't want another seventies Euro project

added to the already complex mix. Kawasaki? A nice idea,

but for yours etc they don't hold quite the same appeal as

an air-cooled six with Honda's often quirky sixties GP

racing history behind it.

So we have it narrowed down to a series. Do we go first naked model circa 1978-79 (above), or second-gen faired generation of 1981-82? Two factors swung the pendulum in favour of the latter: a first-gen naked bike costs 50 per cent or more over its later equivalent and ends up as an investment vehicle; Plus I liked the idea of having the big 'grand tourer' version as it works with the sort of riding I enjoy.

Naked versions are very much on the

international collector radar at the moment and are

growing in value. Meanwhile a well cared-for Prolink, or

CBX1000B or C, will more than likely hold its value.

Honda's CBX1000 six was publicly launched

in late 1977 and an unexpected delay in production meant

it took nearly a year for it to reach the market – so

second half of 1978 for the 1979 model year. It pulled

very positive reviews, but the delay hobbled it in the

showroom. There was a lot going on at the time, such as

the launch of Yamaha's XS1100

and Suzuki's GS1000 series.

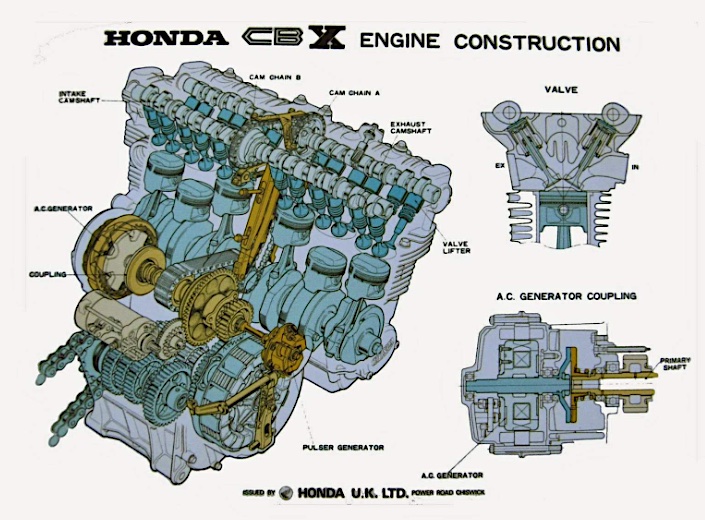

Add in the obvious complexities involved

with a 24-valve inline six, with a carburetor per pot, and

you can understand how a fairly conservative market might

have got a little shy. The first-gen pulled only modest

sales, and so Honda worked on a second that it could shift

into a different market segment.

Rather than just dress it up in new

bodywork, the company put some serious effort in. It

risked knocking a few horses off the top-end to broaden

the midrange and made some small but significant

alterations to the carburetor set-up.

Suspension at both ends was upgraded,

moving from twin-shocks to a Prolink rising-rate monoshock

at the rear. Steering geometry was altered to slow it down

and the wheels were changed over.

When it came to brakes for a now heavier

machine, Honda's showpiece was the fitment of ventilated

discs cast in-house (an impressive undertaking at the

time) combined with an upgrade to two-piston calipers all

round. The previous model was effectively running Gold

Wing brakes with solid discs worked by single-piston

calipers.

The in-house panniers were sculpted to

fit the machine and came with a key-operated one-off

mounting system that worked well.

And then there was the Bol d'Or-theme

fairing, complemented by the long rear tailpiece. It was a

nice try, but the market still wasn't convinced.

In the USA, dealers famously quit stock

for whatever they could get, commonly around 60 per cent

of retail.

And so there we were, a little over 40

years later, with muggins risking a bid at auction on one

of these things. It ended up in the shed.

It came with a cute story. The CBX was

initially sold by Phil Crump Honda in Mildura – yes, the Crump of

international speedway fame. It was owned over the

years by a few people in the district who of course knew

each other.

At some stage, the story goes, the bike was purchased by the wife of one of the gang, who convinced the others to chip in for a restoration including a kangaroo-hide seat. It was presented to the lucky gent as a 50th birthday present.

I got the chance to eyeball the CBX

before bidding and could see it probably needed

recommissioning after a lay-off. It had an aftermarket

exhaust system which was decent quality but was showing

signs of rust. Plus, I wasn't thrilled with the relatively

clumsy pipe bends on the headers (above).

Step one was to do a basic strip (of the

bike) in the back yard and get my head around what we were

dealing with.

Then we did two things: sling it at my

local workshop (the crew at Gassit) and order a bunch of

parts, including a new exhaust system from Delkevic. The

latter is a far better visual replica of the original.

Spares availability for this machine is

mixed. Service parts such as filters are good, but

everything else is patchy.

This turned out to be a pretty big job

and I was fortunate enough to strike a mechanic (Brett)

who was up to the task. In the end, we had to strip down

and clean out the carburetors (a huge undertaking),

replace the plugs and caps, do the usual filters and

fluids, plus rebuild the brake calipers and change the

fork seals. Oh, and then there were the tyres, plus chain

and sprockets. We're talking about somewhere around

Au$4000 (US$2600, GB£2000).

The bill didn't come as a big surprise.

While you'd hope you could just collect the bike, throw in

fresh fluids and ride off into the sunset, machinery at

this level that's been left to sit is going to cost money

to recover. I have a mate in the classic car world who

likes to remind me (when I grizzle about the running costs

of my V12 E31 BMW) that when you get into high-end

machinery, no matter how small the purchase price, you can

expect to cop high-end running costs. He's right. The

trick is to keep it down to a dull roar.

There is an upside. I now know exactly

where the motorcycle is when it comes to condition. That

means you can jump on and head off into the boondocks with

a pretty high degree of confidence.

One of the things I did from day one was

fit the biggest capacity lithium battery you could squeeze

in, along with a charging harness. Bikes in my fleet can

easily end up sitting for a month or two, and it's nice to

not have to root around under sidecovers with ageing and

fragile mounts, looking for charging points.

In this case, the lovely CBX is running a

very full instrument cluster, some of which are

aftermarket. In addition to the fairly comprehensive deck

from Honda we have two temp gauges – one for oil and the

other for the head (reading off a spark plug mount). The

latter two are run by the accessory electrical circuit,

which means you need to be absolutely sure you turn off

the ignition all the way. Otherwise you're greeted with a

flat battery, possibly days or weeks later.

One of the other little tricks we

discovered with this model is it runs two fuel taps. The

main is a traditional item that shuts or opens the pipes,

located on the lower left of the tank, while there is a

second vacuum-operated tap under the tank. The latter is

notoriously unreliable and we've bypassed it. However CBXs

will leak fuel if the 'normal' tap is left on, so you have

to be religious about its use.

After all that effort, what's it like to

ride? Holy heck it's big. This thing dwarfs the Hayabusas

in the shed. It's also heavy – teetering around 300 kilos

fully wet according to the stats.

Firing it up is no issue, though it

doesn't run so much as rasp – there's a hackle-raising

sound which is a little like two angry triples, which you

can put down to a combination of air-cooled straight six

and the lack of balance pipe on the current 2 x 3-into-1

exhaust system. Compared to a current liquid-cooled multi,

it sounds raw and potentially explosive.

Like any older air-cooled engine, it

takes a while to get up to temp, so a long warm-up and

then a gentle ride away works.

Once up to speed, it sounds angry and is

silky smooth – a weird combination. Oh, and it's

alarmingly quick. It might be just 98 horses, but that's

enough to accelerate the thing at an appalling rate,

pulling strongly off the bottom end and very enthusiastic

in the midrange. Top end? It keeps making noise and power,

by which time you've realised this is 1980-something and

not 2020-something, so it's determined rather than

stunning.

As for the transmission, this is a solid

effort from Honda for the period. It's pretty slick and

the clutch has a nice wide take-up band.

Pumped up to the right pressures, the

air-assisted suspension works well – on the plush side and

in this case with a fair amount of damping control.

Steering is slow, which I'm perfectly

happy with on something this size. It still responds to

the handlebars on entry and exit, and feels settled

mid-corner.

Braking? Yeah, well, it's fine for the

period and you need to remain aware of what you're saddled

up with. This thing is heavy and, if you're about to fire

it down a sports road, which it will happily do, it has

limitations.

.jpg)

There are bikes in the broad modern

classic sphere or era that are cheaper and more capable

than the CBX – Kawasaki's excellent GPz900R A1 springs to

mind. I ran one not so

long ago and can recommend it.

As for the CBX, it's fun to jump on these

monsters, particularly once they're sorted. They're big,

fast and clumsy by current standards and hugely

entertaining. Oh, and by the way, in this case the

kangaroo-hide seat is still in place...

Here's a brief engine

start and walk-around vid.

Know your CBX1000s

There

are four variants – two naked:

CBX1000Z – approx 25,000 made

CBX1000A – approx 5000 made (easy ID: second-gen 10-spoke

Comstar wheels)

And two with fairing and

Prolink rear end:

CBX1000-B – approx 3750 made

CBX1000-C – approx 2750 made (easy ID:

it has a solid pillion grab rail at the rear of the seat)

Launch prices

Launch brochure (UK)

Two of the above

illustrations are taken from spectacularly huge and heavy

hardbook The CBX Book vol II, by Ian Foster, 2014

(above). Sadly it's no longer

available through the usual retail outlets, but you may

come across it on the used market.

See an earlier

story on the CBX1000 in our shed

And the period

road test of the CBX1000Z in Classic Two Wheels

Specifications

Honda 1981 CBX1000 Prolink

Good

Fast

Huge presence

Loads of engine character

Not so good

Big

Heavy

SPECS:

ENGINE:

TYPE: air-cooled, four-valves-per-cylinder, inline six

CAPACITY: 1047cc

BORE & STROKE: 64.5 x 53.4mm

COMPRESSION RATIO: 9.3:1

FUEL SYSTEM: 6 x 28mm Keihin carburetors

TRANSMISSION:

TYPE: five-speed, constant-mesh,

FINAL DRIVE: chain

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR:

FRAME TYPE: steel tube, diamond pattern main section, with

engine as stressed member

FRONT SUSPENSION: telescopic fork, air preload adjustment

REAR SUSPENSION: Prolink monoshock, air preload and 3-way

rebound damping adjustment

FRONT BRAKE: 2 x 276mm ventilated discs with 2-piston

calipers

REAR BRAKE: 276mm ventilated disc with two-piston caliper

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES:

WET/DRY WEIGHT: 277/308kg

SEAT HEIGHT: 810mm

WHEELBASE: 1535mm

FUEL CAPACITY: 22lt

TYRES:

FRONT: 100/90-19

REAR: 130/90-18

PERFORMANCE:

POWER: 98hp (73kW) @ 9000rpm

TORQUE: 84Nm @ 7500rpm

OTHER STUFF:

NEW PRICE: Au$5040 + ORC in 1981 (US$3300, GB£2600)

VALUE of a good example in 2024: circa Au$20,000

(US$13,100, GB£10,300)

More on the CBX:

1979 CBX1000A

road test via Classic Two Wheels

Jay Leno video on

the 1981 CBX1000B he's owned since new

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact