Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Our Bikes - Indian Chief Vintage 2009

(updated June 2020)

King Vintage

by Guy 'Guido' Allen; pics by Ben Galli Photography

Adding a Kings Mountain Indian Chief Vintage to the shed - and a little drama along the way...

Every now and then someone will come to me looking for advice on buying their next motorcycle. I suspect this is a little like asking Dracula for a few tips on setting up a blood bank, but it happens.

If what they have in mind is a little obscure or specialist, I’ll usually advise they join a marque club to get an insight into what to look for and, more importantly, get a heads-up on the bikes that often never hit the open market, as they’re sold by word of mouth.

However there are dangers. I joined a local Indian club (ironindian.com.au) some years before Polaris revived the marque. That resulted in the acquisition of one Indian – which is enough for most people. Then there were three in the shed. I may have to leave the club before it causes bankruptcy. Our latest addition is a 2009 Chief Vintage, bought and sold by word of mouth.

The new transport of delight was built at Kings Mountain – the factory bought out by Polaris. Indian at Kings Mountain was actually trading pretty well at the time (2011), building low volume to a high standard – some 1134 bikes in all. In a contemporary interview, we asked former company President Stephen Heese how the firm had been travelling just prior to the sale.

“Brilliantly,” he said. “We were blessed to have recruited a terrific group of people – passionate motorcycle enthusiasts with real experience in the industry. In two-and-a-half years we had a bike on the road. In a year-and-a-half we had a bike in testing, and started producing a year after that.

“We created a lot of happy customers, didn’t have a lot of warranty claims. We attracted a lot of attention. The company wasn’t for sale, and Polaris made us an offer we couldn’t refuse.”

SAME BUT DIFFERENT

So what’s a Kings Mountain? Essentially it’s a Gilroy –

which itself was a clean sheet design circa 1999-2003 –

with a lot more development put into it. The bikes were

hand-built, with total production volume said to be around

the 1100 mark (see list below).

Of those, 500 were Chief Vintage, individually numbered with a plaque riveted to the steering head. (Gilroy did the same with its Chief Vintage.)

Like the Gilroy, this toy has an incredibly long wheelbase at 1737mm, compared to 1625 for the equivalent Harley-Davidson Road King. The steel frame is pretty solid, running Paoli front suspension (41mm shrouded conventional forks) and Fox rear shock – Gilroys ran a KW rear.

Tyre width at the back was bumped up from 130 to 150 to

give it a more current look.

However the big change for the chassis was a much-needed upgrade from a single to twin floating brake discs up front, running four-spot Brembo calipers. This was a welcome improvement on a machine weighing 356kg with a load of fuel on board.

Its heart is a Powerplus 45-degree air-cooled V-twin with two pushrod-actuated valves per cylinder, and self-adjusting hydraulic tappets. Capacity is 1720cc (105 cubic inches), up from 1638cc (100 cubic inches) on the original. Both the ‘bottlecap’ motors are dry sump.

Where Gilroy went wrong on the original Powerplus was with the supplier of its crankshafts. I’m told they went for the cheapest quote, but can’t confirm that. In any case they started failing, breaking crank pins by 5000km at the very latest. This was one problem too many for what was then probably a cash-strapped company and it closed down.

Fixes quickly became available and you can still buy

replacement cranks and even entire engines for a project

bike. Properly built, they have proven to be capable of

decent miles. But the damage to their reputation was too

much.

The approach of the Kings Mountain factory was to take the bike and move it up a level. Externally, lots of details were fixed such as some simplistic design of engine cases, particularly for the timing side of the crankshaft. Everything was smoothed and lots of chrome added. Internally, the quality control was lifted.

In addition to the capacity jump (I suspect for bragging rights and branding rather than necessity), the engine gained fuel injection. That replaced the simple and effective Mikuni HSR42 carburettor, a common fitment to Harleys over the years.

Last, and far from least, was the upgrade from a five to

six-speed transmission by Baker. It’s debatable whether

the extra cog was necessary.

Put the two bikes together – I’m one of the few people who could at the time – and you quickly understand how much Kings Mountain invested in its upgrade. Changes such as paint, instruments, general finish, motor, transmission, brakes, acres of additional chrome, seat, luggage, screen and even little ‘easter eggs’ like branded handlebar end covers abound. They went to a hell of a lot of trouble to make the owner feel good about the purchase.

As a quick example, the perfectly functional if basic leather saddelbags on the Gilroy bike were replaced with a set that has bigger capacity, pockets for incidentals, quilted linings and the whole lot is held on by one of the best quick detach/remount systems I’ve come across.

The investment in build quality and exclusivity was

reflected in the price, which was around US$35,500.

Despite that, the reviews of the day were positive – more

so than for the Gilroy.

BETTER WOMBAT TRAP

With under 300km on the odo when I collected it, the new gizmo qualified as NOS – new old stock. I’ve yet to crack the 3000 mark (hey, there are other toys that need attention too!) but at least have some sort of handle on the plot.

It’s smoother than the Gilroy, though the solid-mounted engine still vibrates. Starting is a little simpler (though has never been an issue on the Gilroy) and the general fuelling is smoother and more tolerant of any clumsiness from the right wrist.

Ride and handling is good, for what it is. We’re talking land-yacht when it comes to steering (look for wide lines in corners), but the suspension rates are well chosen and tend to be firm rather than the floaty experience you get on a lot of equivalent cruisers.

Braking is very good for this class – plenty in reserve

with decent feel. The extra rubber on the rear is a bonus

in this department, given the typical rear-heavy weight

distribution on a bike like this.

There’s a multi-function display built into the speedo dial, with battery charging, trip meters and tacho included, all of which are accessible from a button on the left switchblock.

Performance is decent for the class but hardly head-spinning – we’re talking about 72 horses in a heavy stock package. In reality, what you have is a heavyweight touring cruiser that has some urge, proper brakes, predictable handling and a very nice level of finish.

On the highway it’s bumbling along at about 2000rpm for legal speeds, well below its peak torque and power numbers. So you can drop it down a couple of gears and get something happening when you need to. The trick is to ride the midrange, rather than looking for peak revs.

While the ultra-long chassis makes it a yacht in corners, it allows a huge amount of room for the rider. It fits tall people – yay! Given my usual grumble about how the world is designed for midgets, this is a refreshing change. Oh, and its sheer size gives it enormous presence.

So, good decision? Yep. I really like riding the Gilroy

and have done a lot of miles on it. This, the Kings

Mountain is another level again. It is a better mousetrap.

Given its size, maybe that should be a better wombat trap…

***

JUNE 2020 UPDATE – BCM DRAMAS

The day it went to lunch

One of the dubious joys of owning a limited production bike is there will inevitably be issues and not many people know how to fix them.

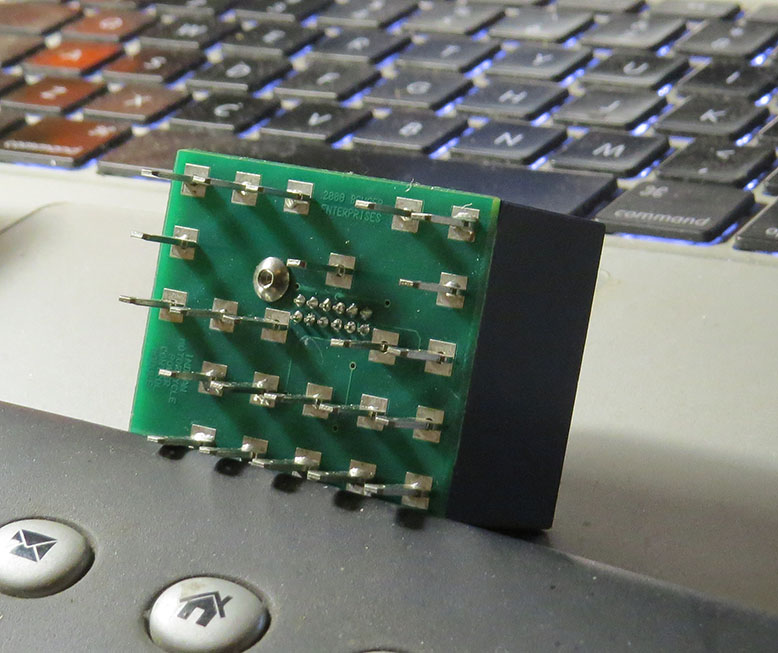

For me, it was the day the bike stopped running. We had some, but not all, lights and no starter or ignition. Back home in the shed, it was simple enough to check the starter itself hadn't failed, by removing the right-side electric motor cover (three bolts) and pushing in the mechanical contact switch with a screwdriver to engage it. This bypassed the starter relay. It turned, but no ignition.

A lot of digging for info revealed there was a recall many years ago on body control modules (essentially an electonic control unit, separate to the one for the engine/injection) and the design had been updated.

You can still buy them as a Polaris part, from America, and the cost is significant at around US$500. While there are local people who will repair body control modules for cars, they run away the minute you say “motorcycle”. Oh well…the new unit did the job and I just ordered a spare. (Call me a cynic...)

The updated part number is, by the way, Polaris 2411878. I got mine through Megazip.net. That's a parts consolidation company and is worth trying if the normal channels aren't working for you.

In the meantime – are there any budding BCM geniuses out there? Drop me a line at allmoto@optusnet.com.au, as I’ve kept the old unit (pictured) and will be curious to see if it can be repaired.

THREE FACTORIES

The three bikes you see here represent the three major factories before Polaris took over and started building them at Spirit Lake in 2014.

Indians are often described by their place of

manufacture, for example Springfield or Gilroy, as a

shorthand for saying which generation and factory they

belong to. The lineage is this:

Springfield 1901-1953

Gilroy 1999-2003

Kings Mountain 2006-2011

Spirit Lake 2013 (for the 2014 model year) to present.

There were other bikes carrying the Indian name sporadically produced between 1953 and 1999, and they were generally rebadged British machines from the likes of Royal Enfield and even Velocette, or the odd minibike producer.

Flying the flag for Springfield in the pic is a 1947 Chief (left).

The all-red machine (right) is a Gilroy Chief Vintage, running the first-generation modern Powerplus motor. Powerplus is an old Springfeld name, revived for this and the next generation bike.

Third (centre) is the Kings Mountain machine from the main feature.

INDIAN DATES

1901 – Indian Motorcycle Company, founded by George Hendee

and Carl Hedstrom, produces its first prototype. It was a

1.75hp single, produced in Hendee¹s home town of

Springfield, Massachusetts.

1930 – Merges with duPont Motors.

1945 – Sold to Ralph Rogers and the Atlas Corporation. The company swings its attention to lighter motorcycles.

1953 – Indian ceases production. The rights to the name are bought by Brockhouse Engineering, which sells re-badged Royal Enfields.

1963-1970 – Floyd Clymer produces a wild variety of machines under the Indian name, though it¹s doubtful he held the rights to it.

1999 – After much bitter court wrangling, an amalgam of nine companies becomes the Indian Motorcycle Company of America, producing out of Gilroy, California.

2000 – The rights to the Swedish-designed four-cylinder Viking cruiser are bought by English musician Alan Forbes, who then owned the British rights to the Indian name. Hand-built production of the design (which replicates an historic inline Indian 4) begins, badged as an Indian Dakota (above).

2003 – Gilroy shuts down, in September.

2008 – A new Indian Motorcycle Company, backed by British finance group Stellican (which also revived historic boat brand Chris-Craft), buys the Gilroy design and starts production of an updated version at Kings Mountain, North Carolina.

2011 – Polaris, maker of Victory brand cruisers, buys Indian in America.

2013 – Production of the Polaris machines begins, for the

2014 model year, at Spirit Lake, Iowa.

KINGS MOUNTAIN PRODUCTION

2009 460

2010 340

2011 109

2012 140 Polaris Built

2013 85

LE Models 35

FE Models 25

Other 25

Total KM Design bike production 1134

(Figures from Mark Moses)

SPECS

Indian Chief Vintage 2009

ENGINE:

TYPE: air-cooled, two-valves-per-cylinder, 45-degree

V-twin

CAPACITY: 1732cc

BORE & STROKE: 101 x 108mm

COMPRESSION RATIO: 9:1

FUEL SYSTEM: sequential fuel injection

TRANSMISSION:

TYPE: Six-speed, constant-mesh,

by Baker

FINAL DRIVE: Toothed belt

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR:

FRAME TYPE: Steel cradle

FRONT SUSPENSION: 41mm conventional telescopic fork by

Paoli

REAR SUSPENSION: single prelo-adjustable shock by Fox

FRONT BRAKE: twin floating discs with 4-piston Brembo

calipers

REAR BRAKE: single floating disc with 2-piston Brembo

caliper

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES:

WET WEIGHT: 356kg

SEAT HEIGHT: 708mm

WHEELBASE: 1737mm

FUEL CAPACITY: 21.2lt

WHEELS & TYRES:

FRONT: 130-90-16

REAR: 150/80-16

PERFORMANCE:

POWER: 54kW (72hp) @ 5000rpm

TORQUE: 136Nm (100lb-ft) at 3000rpm

OTHER STUFF:

PRICE WHEN NEW: US$35,500

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact