Motorcycle Investor mag

GSX legend

Our bikes – 1980 Suzuki GSX1100E

February 2011, updated 2026

by Guy 'Guido' Allen, pics by Ellen Dewar

Fancy a big, cheap, powerful naked bike? Guido did and reckons he found just the ticket in an old Suzi

“Do we own that?” enquired Ms M snr, who was stabbing a

somewhat suspicious finger at Grendel, the GSX. I briefly

toyed with the idea of denying everything, but it’s a

tough call when you’re caught, polishing rag in one hand

and an old motorcycle in the other. You see, I hadn’t got

around to letting her in on the joyous news that yet

another motorcycle had been added to an already bulging

shed.

“It looks good,” she announced, before toddling off to

wreak havoc on some unsuspecting sector of what’s

laughingly called a garden at our house.

Like many of the monsters in our fleet, this one was bought almost by mistake. I wasn’t really in the market, but tripped over an ad for this thing, asking $4500 (this was 2011). The thinking was that, despite there being hoardes of two-wheeled transports of delight at our disposal, there wasn’t anything that would qualify as a nice easy-going all-rounder that you could just sling a bag on and head interstate with.

So if we could get this one for a good price, it was a candidate. An offer of $3500 was made and accepted. A week or two later, the bike was shipped across from Tasmania.

Now is probably a good time to mention that I bought this sight-unseen from a Kawasaki wrecker – not the most promising start. But it looked pretty complete in the photos and I was told that it was a decent runner. With just a little trepidation, I hopefully stabbed the starter button for the first time. Yep, it fired and sounded pretty solid. Beaut!

The GSX series

Suzuki’s GSX1100 series was effectively the company’s

second line of big four-strokes. It all started with the

GS two-valve family, which went on to be sold alongside

the GSX for several years.

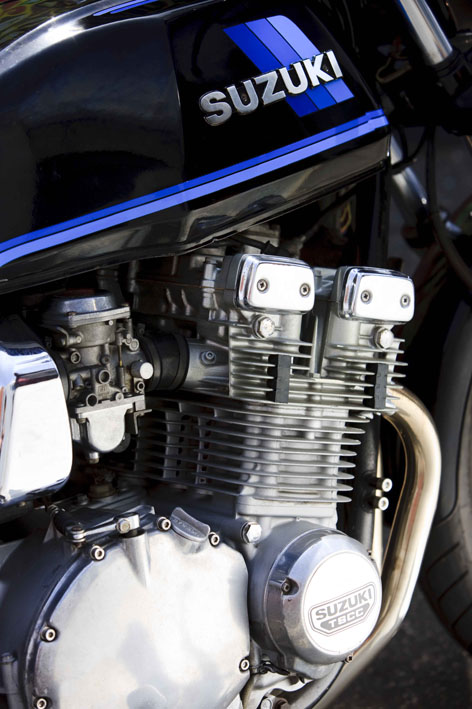

The GSX (confusingly known as the GS in the USA) was a big, bluff, motorcycle wrapped around a particularly robust four-valve air-cooled powerplant. It started off with 1074cc capacity for the 1980 model year, claiming 100 horses.

It powered a series of motorcycles, including the Katana, and grew to 1135cc and a claimed 124 horses by the time it was shoe-horned into the last of this series – the GSX1100EFF of 1985-86.

By far its biggest claim to fame was strength. It was hugely popular with engine tuners, thanks to an apparently unburstable bottom end, and has been a major force in the drag bike world.

It also saw a resurgence in historic racing. Last January at the Phillip Island historic challenge, Steve Martin set a sub-1’40” time on a Katana, rumoured to be punching out somewhere up near 190 horses. That time would have landed him toward the pointy end of a superbike grid, not so long ago.

The engine is straight-forward to work on. Valve lash is set via screw and locknut, with most tasks being easy to reach once you remove the fuel tank.

The bike you see here is the first of the 1100 series, the GSX1100ET. In its day, it could briefly lay claim to being the fastest production bike in the world, with a top speed of 220km/h, and a quarter mile time in the 11-second range.

It went on to a respectable race career. In its first Castrol 6-Hour, in 1980, it was beaten by the comparatively exotic Honda CB1100R, settling for second place. With the Honda out of the way the following year, it scored first and second. By 1982, the Katana had taken over the 6-Hour duties.

Though it had more than its share of success, the GSX is actually fairly conventional. The chassis is based on a twin-loop steel frame, running a 19-inch front wheel and 17 rear. Suspension has a lot of adjustment on hand, with air-assist for the springing at the front, mechanical preload on the rear, and damping options at both ends.

It’s a heavy sucker. Weighing 243kg dry, it carries a useful 24 litres of fuel. Typical of the era, it’s roomy, with plenty of space for two people and a comfy seat. It’s the quintessential Universal Japanese Motorcycle – serious performance bike for its day, easy to live with on a daily basis, and pretty good touring potential.

More parts, Vicar?

While I was generally happy with Grendel, there was a fair

bit of work to be done. The big relief is the powerplant,

with a little shy of 70,000km on the odo, is just fine –

noisy if the idle is allowed to drop too low, with clutch

basket and primary drive making a racket, but that’s

fairly typical.

It arrived with a very sad-looking old four-into-one exhaust, weeping fork seals and suspect front brakes. Also, when you hopped aboard, the footpegs were out of alignment. Then there was the usual cosmetic wear and tear from three decades.

I’d promised not to get carried away with this one. The theory was it was supposed to be cheap transport. Plan A was to get a reasonably powerful naked bike on the road for under $5k. The added bonus was it’s old enough to go up rather than down in value, and to be registered on historic plates at a fraction of the normal cost.

As you might expect there were one or two surprises. The bike came with what was supposed to be a used and slightly battered standard exhaust system – a major bonus, if it could be cleaned up. Oops – it turned out that half the system was for a GSX750, which looks identical, but doesn’t fit. Never mind, I knew it was too good to be true.

Stock exhausts can’t be found for love nor money, so we went on the hunt for a replacement four-into-one. I really like the look of the Marshall Deeptone (UK), but it wasn’t available at the time.

In the end, I settled on a Motad. British designed and, I suspect, Chinese-made, it landed at a ridiculously low $550. The quality is acceptable, rather than brilliant, and has dropped a little since the manufacturing moved out of the UK. The fittings are a little tacky, but the whole set-up looks fine once it’s on the bike. The muffler hangs lower than ideal, something which became evident when I tapped it on a lane marker during the photo session, putting a slight dent in the system.

Whinges aside, the system is fairly quiet and the performance is good. It would have been nice to get a decent four-into-two made, to match the original layout, but that would have comprehensively blown the budget.

There are lots of original parts available. Mick Hone

Motorcycles in Melbourne has been a useful source,

with a surprising amount in stock. When I wasn’t harassing

them, I was using my local dealership – Stafford

Motorcycles – for the mechanical work. Both shops are run

by experts with a strong race background who’ve been

around since GSXs were new, which means they ‘get’ them.

The dud footpegs were easily replaced (three out of four were available), while the fork seals were straight-forward. The box of bits that came with the machine included a Chivos fork brace – a great lump of alloy designed to add a little rigidity to the front end. This is the second early eighties Suzuki I’ve bought with one of those things included – they must have sold hundreds of them. Anyway, I’ve left it off. To me, it’s just adding whipped cream to a turnip.

The rear suspension is aftermarket Konis, which seem to be remarkably fresh. They were set to maximum everything and have now been backed off for a little more compliance.

Stafford’s workshop crew pronounced the front brake master cylinder to be pining for the fjords and recommended replacing it. They ended up sourcing a complete aftermarket unit for just $140, which was cheap enough to discount any thought of getting a wrecked part. It’s not exactly the same as the original, but fits in with the general look of the GSX and works fine.

It’s remarkable how much you can improve the appearance of a motorcycle just by getting stuck into the details. Grendel was unquestionably tired in the visual department, but the paint is sound (if a little chipped in places) and all the cosmetics are there. The rear mudguard had a mysterious ‘bite’ out of one side, but was replaced fairly cheaply with a new part.

Initially I wondered about the poor match-up of the pinstripes at the bottom edge of both sides of the fuel tank, until a period brochure revealed that that’s how they came out of the factory…

So it was time to get busy with the touch-up paint. The black paint is simple enough to restore (albeit not perfectly), while the broken chrome strips on the instruments and rear cowl were tidied up with a silver paint pen. Purists will be horrified, but it looks fine when you stand back a little. Throw some polish at it, and the whole shebang brushes up well.

Mount up

This is my second GSX – the last was a more comprehensive

restoration/hot-up job in the late eighties and I hadn’t

ridden one since. It’s funny how our mental goal posts

have been moved over the intervening period, by behemoths

like 1800 GoldWings and 2.3 litre Triumphs. There was a

time when the GSX seemed like a massive bike – not any

more. It’s not exactly going to blow away, but it’s really

only a middleweight contender.

The mental image I had was wrestling an unsorted pig-rooting monster through the bends, wondering who was going to make it out the other side. While it could use further fettling – with fresh rubber at the top of the list of priorities – it’s not bad. Okay, if you threw it into a corner at GSX-R speeds, you might as well pre-book the ambulance to save waiting. But it’s still a hoot. The cornering clearance is limited and the braking leisurely, though the steering is nice and easy thanks in part to the upright ride position and big wide handlebars. It’s low stress fun.

The power is ample. GSX engines of this era have a ton of midrange and pretty smooth delivery. I suspect this one could do with a carb-sync, but it’s got more than enough oomph to give the police reason to tear up your licence.

An hour or so playing with the thing in the backblocks had me walking away with a big grin across the dial. It’s just good old-fashioned petrol-head fun, like it used to be. You’re not doing lap-record speeds but, then again, you could sling a swag across the pillion seat and head off across the continent tomorrow, without a worry.

Excluding normal running costs like servicing, I reckon Grendel came in under budget – given the grin factor, that’s great value.

Know your enemy

Before embarking on a project like this, it really pays to

do your homework. I’ve owned one of these bikes before and

have several other machines of a similar vintage, and so

knew what I was getting into.

If you’re not familiar with the territory, get online and on the phone to see what parts are available at what price. The GSX bits were pretty reasonable, which isn’t always the case. It’s typical for cosmetic pieces and exhaust systems to be unobtainable for this era, or viciously expensive.

Also have a think about what you plan to do. Is it just a quick tidy-up and ride, like this project, or a full resto? Keep in mind budgets and timelines for full restorations often blow way out and then there’s the question of whether the machine is worth all that expense.

There are still workshops out there that happily deal with this older machinery, but many do not. So if you’re not prepared and able to tackle the mechanical tasks yourself, suss out what support is out there.

It also pays to get to know the history of any model

you’re looking at, as it will help enormously when you go

to source bits. In the case of old Suzukis, you’ll find

this site a great starting point: suzukicycles.org.

And here is a bit of trivia: GSX1100Es came first and

second in the 1981 version of the legendary Castrol 6 Hour

production motorcycle endurance race

See more Our Bikes stories here

SPECS:

GSX1100ET 1980

ENGINE:

TYPE: Air-cooled, four-valves-per-cylinder, inline four

CAPACITY: 1074cc

BORE & STROKE: 72 x 66mm

COMPRESSION RATIO: 9.5:1

FUEL SYSTEM: 4 x 34mm Mikuni CV carburettors

TRANSMISSION:

TYPE: Five-speed, constant-mesh,

FINAL DRIVE: Chain

CHASSIS & RUNNING

GEAR:

FRAME TYPE: Twin-llop, steel

FRONT SUSPENSION: 37kmm Kayaba fork with spring + air

preload + rebound damping adjustment

REAR SUSPENSION: Kayaba dual shockls with preload and

rebound damping adjustment

FRONT BRAKE: 2 x 275mm disc

REAR BRAKE: 275mm disc

DIMENSIONS &

CAPACITIES:

WET WEIGHT: 254kg

SEAT HEIGHT: 806mm

WHEELBASE: 1440mm

FUEL CAPACITY: 20lt

TYRES:

FRONT: 120/70-17

REAR: 200/50-17

PERFORMANCE:

POWER: 73kW (100hp) @ 8700rpm

TORQUE: 85Nm (63ft-lb) @ 6500rpm

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact