Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Meet Hannibal

Our Tainton-tuned first-gen Suzuki

Hayabusa

by Guy ‘Guido’ Allen, pics by Lou Martin (November 2020)

Though it's been on the market a couple of times, Hannibal our hotted-up Hayabusa has somehow managed to survive assorted culls and is now a fixture

It was a bit of a shock to wander past Hannibal the Hayabusa in the shed the other day and suddenly come to the realisation that it’s 21 years (1999) since I first threw a leg over one and a whole 17 years or so since I picked up this example from Suzuki and failed to return it. You see big performance bikes traditionally go through a lot of owners and, by now, Hannibal should have had at least four of five.

Why? I suspect it has to do with fashion. Bikes like the Hayabusa start out as the biggest and fastest thing on the block and find themselves being used as a trade-in soon after something faster and newer lands in the showrooms. From there, they tend to go through owners every two or three years, each of which tends to be less well-funded than the previous, which means the bike ends up a somewhat tired example of its former self.

Old mate Spannerman depends on this trend, as he refuses to pay more than $1500 for a motorcycle, no matter how quick it is. Can you imagine what a $1500 Haybusa would feel like? The brakes, steering and suspension will be clagged, but it will still do well over 250km/h!

Hannibal has somehow defied the trend, though that’s been down to luck rather than good management. I’ve actually had it on the market several times, until some would-be purchaser has irritated me to the point they can’t have it at any price or, in a couple of cases, I’ve made the mistake of taking it for a ride and enjoyed it so much the toy has been promptly withdrawn from the market.

To recap for those who were busy at the time, the Hayabusa was launched as Suzuki’s hero muscle bike in 1999. Its claim to fame was a top speed in excess of 300km/h (around 305 was typical), matched to what was at the time somewhat shocking styling and a 175 horsepower figure.

We were assured the organic curves were the result of serious wind tunnel work, and it took a long time for many of us to get accustomed to the look. In any case Suzuki successfully over-shadowed the more civilised Honda Blackbird (it could ‘only’ manage 290km/h and 164 horses!) and had a big hit on its corporate hands. One that has gone on to qualify as a cult bike.

The first-gen Hayabusa underwent some minor changes, including some early mods to the rear subframe. Most controversial was the 2001 model year agreement between the major bike makers that they would limit their product to 300km/h. In the case of the Hayabusa, this meant an electronic limiter with the visual give-away that the speedo numbering stopped at 280.

In 2003 we saw the installation of a higher-spec engine control unit that boasted 32-bit processing for more precise fuel metering, plus a lighter generator rotor.

It took until 2008 for Suzuki to launch a redesigned ’Busa, with updated styling, chassis and engine.

As for Hannibal, it comes from a generation of bikes that was almost universally modified. While many owners were content with a set of slip-on mufflers and a potential modest lift in performance, others went the whole hog with wild engines (300hp-plus turbo versions are surprisingly common), lengthened swingarms, you name it.

For me the rot started when Don Stafford popped under his shop counter and emerged proudly bearing a titanium header and collector set from an Over Racing four-into-one system. It was unbelievably light – what it weighed seemed to defy logic. The paper-thin walls and welds were something to behold and it almost seemed a shame to hide them away under a fairing. Of course, before I knew what had happened, muggins was wandering out the door with a shiny new system, including a carbon-fibre muffler.

Along the way, I quietly fitted an electronic deristictor that bypassed the factory top speed restriction.

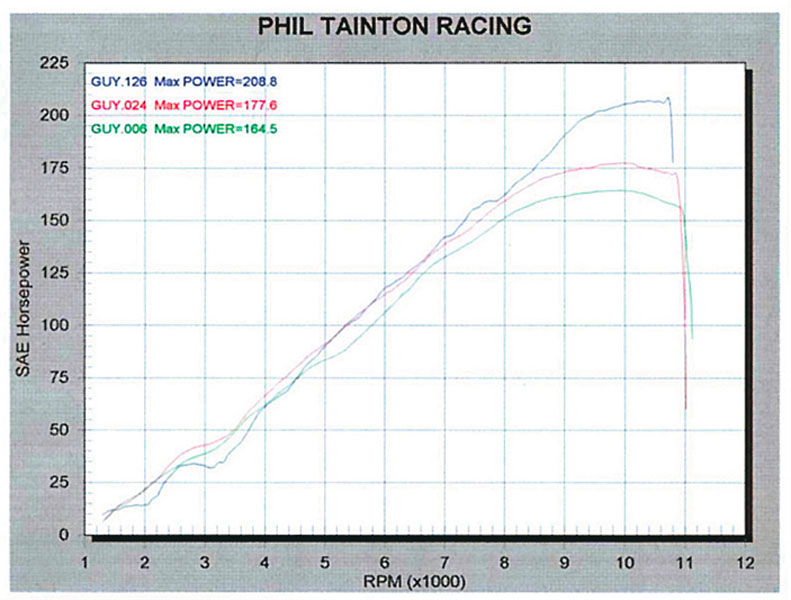

The Over system and Hannibal found themselves in the workshop of Phil Tainton Racing, the kitchen that had for years been producing Suzuki Australia’s successful superbikes.

With the addition of a Dynotech tuner, Tainton managed to get the rear wheel horsepower up from an already very healthy 164.5 to 177.6. Add an estimated 15 horses for normal losses on a machine like this and you’re talking around 190hp at the crank. What’s more, it had boost literally everywhere in the rev range with a significantly ‘fatter’ torque curve.

Now that’s where we probably should have left it alone, with enough grunt to conduct a moon launch, but where’s the fun in that? So I started making noises to Tainton about getting serious with the power and he was more than happy to take up the challenge.

With new pistons, one-off camshafts, a port and polish, plus a host of other sometimes very subtle mods, the bike was now a monster with 208.8hp at the rear tyre, or over 220 at the crank. Tainton was actually annoyed, as he was shooting for 210 at the wheel, but his cause was probably held back a little because the Over Racing muffler was quiet enough to be street legal. Something a little more open might have been enough to get the additional urge he wanted.

Still, we’re talking a fair effort – 220-odd horses was then a long way ahead of any stock road bike and remains up there over 15 years later. The way it develops its power is entertaining. It lost some of the classic Hayabusa low-end grunt, though it would still match a 2017 GSX-R1000. Up top is where it got really interesting. At 8000rpm it was making as much as a stock ’Busa at full noise. In the next 2000rpm, it was picking up an extra 45-ish horses. Those last couple of notches on the tacho are pretty entertaining!

As for top-speed, Tainton reckoned it would be good for 330km/h so long as you fitted the right gearing.

And now? Hannibal has aged pretty well, though compared to more current machinery it succeeds with brute force rather than finesse. While running good suspension, it’s a fairly long and heavy bike and can sometimes feel like it. The low profile counteracts that to some extent, so it’s far from being overwhelming.

The one thing that disappointed a little from day one was the front brakes. Six-spotter calipers can’t help but look impressive, but these are more bark than bite. Though they rate as adequate, they’re nowhere near as sharp as current kit. Replacing the synthetic rubber hoses with braided steel made a significant improvement.

Reliability has not been an issue, despite all the modifications – it’s an argument for making sure the work is professional. Admittedly it’s only done around 18,000km, plus a lot of dyno time! The only issue I’ve struck is an ongoing struggle to get the titanium headers to seal properly – an annoyance unique to this bike.

Servicing costs are the same as for any other Hayabusa, though this engine has a monster appetite for fuel. Where a stock first-gen Hayabusa can be expected to get 16km/lt when ridden gently, this one struggles to get 12 and that can easily drop to 10, or under 8km/lt if you get throttle-happy!

The days when Hannibal would be put up for sale every time I needed cash have gone. It’s become part of the furniture of my life and we’re pretty well stuck with each other.

As a second-hand buy, you could do a whole lot worse than

one of these things. In some ways they’re a victim of

their own success, with lots of examples being offered. In

turn that keeps the prices down.

See our Hayabusa

buyer guide covering Gen 1 & 2

And our Hayabusa

resources page

Standard Spex

Suzuki GSX1300R Hayabusa (1999-2007)

Type: Liquid-cooled in-line four with four valves per

cylinder

Bore and Stroke: 81 x 63mm

Displacement: 1299cc

Compression ratio: 11:1

Fuel system: Electronic injection

TRANSMISSION

Type: 6-speed constant mesh

Final drive: Chain

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR

Frame type: Twin-spar alloy

Front suspension: USD fork, full adjustment

Rear suspension: Monoshock, full adjustment

Front brakes: Twin 6-piston Tokico 320mm twin discs

Rear brake: Single disc

Front tyre: 120/70-17

Rear tyre: 190/50-17

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES

Dry weight: 217kg

Seat height: 805mm

Fuel capacity: 21lt

PERFORMANCE

Max power: 175hp @ 9800rpm (stock)

Max torque: 141Nm @ 7000rpm (stock)

Good

Loads of performance

Robust

Lots of tuning potential

Not so good

Front brakes not sharp

Web links

Australian-hayabusa-club.com

– local owners

Busanation.com – Facebook forum

Suzukicycles.org

– excellent database of Suzuki models

See the Classic Two Wheels Hayabusa test from 1999

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact