Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Our bikes - Yamaha GTS1000, part 2

(June 2020)

by Guy 'Guido' Allen, pics by Stuart Grant

See part 1, buying the bike, here.

Raising the Dead

In what turned out to an ugly exercise, we eventually

bring out the hidden gem from under a dustsheet…

But for a stroke of luck, this bike would not exist. Rather than being ridden up a tree, or thrashed into immobility and sent to the tip, this machine ended up under a drop sheet in the corner of a warehouse, unloved and forgotten.

In any case, this GTS sat for many, many years until it

was unearthed again last year. I’d heard of its existence,

but it was nothing more than unsubstantiated rumour

despite something like a decade of nagging people who

might know.

Fifteen years after it left the factory, I got a phone

call. “Y’know that motorcycle you’ve been hassling me

about? Come and get it. Now.” So it once again saw the

light of day, with a mere 600km on the clock and no keys.

It looked good on the trailer, but heaven only knew what

monsters lurked under the bodywork. As it turned out, my

sense of slight dread was well-founded. There was one

compensation: it was engine and chassis number one.

BOLD INTENTIONS

There’s no question that Yamaha had bold intentions when

it first penned the GTS1000. It was to be the corporate

techno flagship, with ABS in some markets (very unusual in

a Japanese model in those days), fuel injection, catalytic

converter and the real icing on the cake – a version of

James Parker’s RADD (Rationally ADvanced Design) front end

combined with a radical and low-slung omega-shaped main

frame.

The front end was developed on the tail end of a period when every man and their dog seemed hell-bent on developing an alternative to the fork which, some engineering purists will assure you, is/was old-hat and not in the least bit clever or even terribly effective. There had to be a better way.

Of course we’d seen the Elf project contesting the world GP series, with Rocket Ron Haslam at the handlebars. It did okay and a version of the centre-hub steered design was trialled on the road by Bimota with its adventurous Tesi.

USA inventor Parker came up with his own variation, running a dual swingarm system, fitted it to an FZ750 road bike – an exercise called the MC^3 that gained enormous world-wide publicity. The claimed advantages included less steered mass, greater rigidity, separation of the steering and suspension forces, and a better distribution of the latter to the frame.

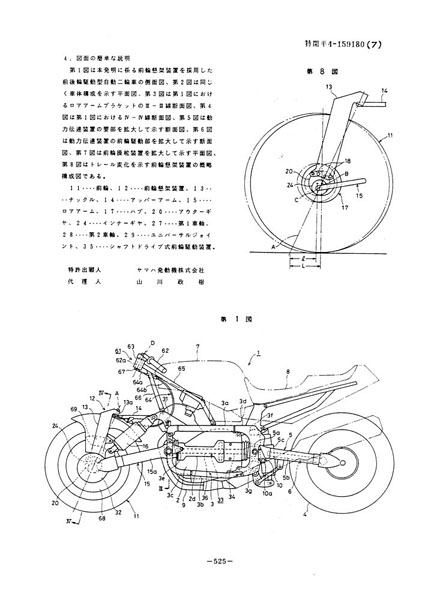

Yamaha licensed the idea (which it described as hub link steering) and, with Parker as a consultant, turned it into reality. Note that in the patent application drawings above, the company was toying with two-wheel drive!

Though Parker clearly had sporting ambitions for his design, Yamaha took a more conservative route, developing it with a flagship sports-touring chassis in a machine clearly designed to do two-up work.

At the time, there had also been talk of a voluntary power limit among bike manufacturers of 100 horses. It never really held the proverbial water, but was strong enough an idea to encourage Yamaha to detune its premium FZR1000 sports engine (a five-valve per pot design) to meet that limit.

Though the new machine was a guaranteed headline-grabber in 1993, the response when it actually hit the market was less enthusiastic. It was not super fast, was surprisingly big, weighed a bit at 251kg dry, and most critically was very, very expensive. Given the market was already leery of the ‘weird’ front end, the price of over $22,600 (US$15,400, GB£12,150) plus tax and registration was just too steep. This was at a time when a top-flight litre-class sports bike cost $15,000 (US$10,200, GB£8000), while a 1500 Goldwing was priced at $25,000 (US$17,000, GB£13,500).

It struggled for traction in most markets and bombed in Australia. The figures are near impossible to find, but the popular wisdom is that about 33 were sold here, while many bikes intended for Oz were diverted elsewhere. (One former trade figure said that GTS came to be known in the trade as shorthand for gone to Singapore.)

LET THE DRAMAS BEGIN

So what happens when a new project bike hits the shed?

Getting a set of keys was the big priority, which

necessitated removing the upper triple tree complete with

the theft-proof ignition barrel and finding a locksmith

willing to cut a new set. This turned out to be the

easiest and least expensive job in the whole operation.

Then I scored a new battery, tossed some fresh fuel and oil into the appropriate holes and rather optimistically switched it on. The good news was the complex electrics seemed to be in good working order – or most of them. I couldn’t help but chuckle at the size of the beast’s electronic brain – massive compared to today’s kit.

While the GTS would turn over it clearly had no intention of running. And then there was the smell of rotten petrol. So what happens when you leave unleaded fuel sitting in a complex motorcycle for 15 years or so? It essentially eats everything it can weasel its way into. We ended up having to ditch the fuel tank, the lines, the pump, the injectors…pretty much everything between the filler on the tank and the cylinder head. This is not a job for the faint-hearted or someone with shallow pockets. And I have both afflictions. It’s a clear warning to anyone storing a bike over the long term: ditch the fuel.

Luckily I had the assistance of the good folk at Stafford Motorcycles, whose Yamaha knowledge turned out to be invaluable. And, bless them, Yamaha Australia had plenty of spares which they were probably happy to see sold.

Okay, so the fuel system dramas were disappointing, but they were compensated for by an incredible run of luck with a couple of Motorcycle Trader readers. A gent in Sydney turned out to be a former Yamaha staffer who kept some of the original promotional material, including a rare corporate video, and sent it down with his blessing. Another gent in rural Vic pitched in with a CD loaded with copies of brochures, specs sheets and, most importantly, workshop manuals. Neither wanted recognition or compensation.

The rest of the machine was a remarkably easy fix. New tyres, oil change and filter, a few miscellaneous bits plus a touch up for some of the panels and it was ready to go. Or was it?

ON THE ROAD

I’ll admit to some trepidation when the workshop fired it

up for the first time. Let’s face it, it should run, but

there was plenty more capacity for surprises. Nothing

reared its ugly head.

I briefly rode the original magazine test bike way back

when this thing was first released and remembered walking

away with mixed feelings. My relatively brief ride around

town had highlighted its bulk, and not a heck of a lot

else in the way of virtues.

That being the case, you might wonder why the hell I went

to so much trouble to track this one down. Well, it was the

techno flagship for its day. Yamaha has often been a

courageous maker (for example, the only mainstream one to

so far sell a two-wheel-drive) and this was a classic case

of the company sticking its neck out. Example number one

was definitely collectible.

So, is it a decent ride? It’s an odd experience having to

run in a 15-year-old motorcycle, but with a couple of

thousand kays under its wheels the thing is turning out to

be a treat. What I didn’t get to experience of a decade

and a half ago is just how uncannily smooth it is on the

highway.

The power, though not huge, is more than enough and in the

right place – there’s ample midrange. Its ride position is

slightly lean forward, which works when you get up a

reasonable speed, while the suspension and long wheelbase

combine to be very comfy.

Downsides? It’s a big heavy motorcycle, and hardly what

I’d call a lithe handler. That said, once you get your

head around the fact it likes to be given assertive

directions from the handlebars, it tips in nicely and is

exceptional in the way it holds a line. Mid-corner bumps

have sod-all effect and this is probably the most stable

motorcycle I’ve ridden through a curve.

They quickly scored a reputation in the UK for being

thirsty, which is the case if you’re up it for the rent.

Then again it’s still no match for Hannibal, my hotrod

Hayabusa, which regularly returns a mere 8km/lt. Ridden

somewhere near the speed limit, the GTS in fact manages a

respectable 16-17km/lt.

This example has the very early seat, which isn’t

brilliantly padded – the company quickly changed the

material as they hit the showrooms.

Steering is light but slow, while braking is reassuringly

good. The built-in anti-dive tendency of the front end

results in you getting a slight dip at the snout and a

very reassuring attitude as you haul on the anchors. For

its size and age, it does very well in this department,

with the centrally-mounted single six-piston front disc

providing plenty of feel and bite.

While I should arguably leave the monster parked in the

shed, given the fact its numero uno of a rare breed, I

figure it spent enough of its life resting and, they are

meant to be ridden aren’t they? As it turns out it’s too

good a touring companion to be parked – so Yamaha got that

part of the brief right.

Given its peculiar history, naming it turned out to be

easy. What do you call a bike that shouldn’t exist?

Casper, of course…

***

One good ride

There was one ride on this thing that suggested Parker et al were on to something. On the way back from a destination hundreds of kilometers from home, rain started pouring down. So, slick conditions and lots of corners.

Despite the conditions, the GTS proved stable and the front end really 'talked' to the rider. It was entirely predictable and fast. On the day, nothing could have kept up with it. A big statement? Probably, but it was a jet and left a lot of better riders in our wake.

***

Good

Ultra stable

Smooth

Good travel companion

Not so

Very expensive in its day

Too weird for some

***

Great expectations

Could or should the GTS1000 have gone on to greater

things, if pricing and market reluctance had not defeated

it? Possibly. James Parker (at left above), the designer

of the front end, comes across as being a touch bitter

about how quickly Yamaha backed out of the project.

He obviously had high hopes for his creation, which he

felt was a natural for two-wheel-drive, and he in fact

patented such a set up. Parker has gone on to design a

third-generation front, and says he is in discussions with

another maker about its use.

One thing we do know, however, is that time has been kind to the reputation of the GTS. There was a remarkable decision by Bike magazine in the UK to name the model as the coolest of rare motorcycles, in December 2006. That’s ahead of exotica such as the Norton F1 rotary.

The rather generous write up said: “Bold, daring, peerless, Yamaha's GTS1000 is the embodiment of unconventionality. Shaking off almost a century of tradition, the tourer junked regular telescopic forks for a huge aluminium swingarm working a monoshock, with hub centre steering and a low, arching Omega frame system.

“The Terminator films were still current when the GTS was launched and the single-sided front end had a firm futuristic look to it, blending into the clean, uncluttered, enclosing bodywork to give a glimpse of the biking in the future.

“Unfortunately the alien appearance, frankly excessive weight and a steep asking price limited sales – but they don't matter one iota today. This is still ground-breaking and courageous engineering…ride a GTS and you're also on a bike unlike any other you'll see – with so few sold, the chances of matching T-shirt syndrome are almost nil. Scarce stylish, yet capable and completely useable: that's cool in our book.”

SPEX

ENGINE

Type: Liquid-cooled inline four with five valves per

cylinder

Bore and Stroke: 75.5 x 56mm

Displacement: 1002cc

Compression ratio: 10.8:1

Fuel system: Electronic injection

TRANSMISSION

Type: 5-speed constant mesh

Final drive: Chain

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR

Frame type: Omega-shaped main member

Front suspension: Parker swingarm

Rear suspension: Monoshock, preload adjustment

Front brakes: Single 330mm ventilated disc with six-piston

caliper

Rear brake: 282mmdisc, two-piston caliper

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES

Dry weight: 251kg

Seat height: 795mm

Fuel capacity: 20lt

PERFORMANCE

Max power: 100hp @ 9000rpm

Max torque: 10.8kg-m @ 6500rpm

OTHER STUFF

Price new: $22,600 plus ORC

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact